A few days ago, I read the article “Finding Sparks Rethink of Russo-Japan War” in the Yomiuri (Link to original article HERE). According to some new documents discovered by University of Tokyo historian Wada Haruki, a key Russian politician attempted to propose an alliance with Japan in the days leading up to the Russo-Japanese War. The article reports that Aleksandr Bezobrazov, a man who has long been considered an advocate of the conflict, first communicated the draft “to Japan’s Foreign Ministry by telegraph on Jan. 1, 1904, by a Japanese diplomat in Russia. The diplomat reported to the ministry in detail about the proposal 12 days later…Despite the tip, Foreign Minister Komura Jutaro met with Prime Minister Katsura Taro, along with the ministers in charge of the army and navy, on Jan. 8, when they agreed to initiate hostilities.”[i] The article concludes that this new finding could lead to a revision of the widely-accepted interpretation that Japan was goaded by Russia into starting the conflict. This may also attract attention in Japan because NHK just started airing a three-year drama series based on a saga by novelist Shiba Ryotaro that depicts the Russo-Japanese War as one of self-defense by Japan.

Reading this article, I thought of three things:

- The document was communicated on January 1st and then reported to the ministry in detail 12 days later. That means the report was on January 12th. If Foreign Minister Komura and Prime Minister Katsura decided to initiate hostilities on January 8th, it is questionable how much they knew about these overtures from Russia. But that’s just nit-picking on my part and this is no doubt something that will be explained further in the two volume book Professor Wada will be publishing.

- Even if Komura and Katsura had full knowledge of Bezobrazov’s attempt to create an alliance (which is unlikely), I doubt it would have dissuaded them from initiating hostilities with Russia. It is also unlikely that this finding will change the interpretation that the Russo-Japanese War was fought as a defensive war. While Russia may not have been planning any attack against Japan, it is quite clear that Japanese leaders at that time believed they were acting in defense of Russian actions. This is due to Japan’s perception of the international system during the early 20th century and the way it conceptualized its own security. However, this new discovery can reinforce the interpretation that the Russo-Japanese War was a preventive war rather than a preemptive war.

- Can preventive warfare be considered defensive? Should preventive war be used to achieve foreign policy goals?

The Russo-Japanese war began on February 8th, 1904 with a night attack on Port Arthur. This attack was made before Japan declared war on Russia. The preemptive nature of the attack was critical not only to the success of the siege (the Japanese forces caught half of the Russian fleet at anchor in the harbor) but also to Japan’s victory. Two Russian destroyers were on picket duty and suddenly found themselves under attack by ten Japanese destroyers. The Russian ships turned and hauled into the inner harbor to warn the fleet (it was night and they had no radios). However, as the Russian ships pulled in, Japanese were right on their tail so the warning was pointless. The Japanese destroyers proceeded to shell the Russian battleships and cruisers, which were still at anchor. Most Russian ships had not deployed torpedo nets and many of the officers were on shore drinking. In other words, the Japanese caught the Russians with their pants down. Togo then mined the outer harbor, which effectively trapped the Russian Pacific fleet in Port Arthur. While most of the damage inflicted on the Russian ships was repaired, the attack on Port Arthur – like the attack on Pearl Harbor – had a profound psychological effect. In a single stroke, Japan announced to the world that it had become a great power. They were instantly given respect (or, at the very least, recognition), especially from Great Britain. This respect only increased the following year when, after the decisive Battle of Tsushima, Japan earned the honor of being the first non-Western power to defeat a Western country in a military conflict. Back in Russia, the surprise attack created a nationalist uproar as citizens screamed for vengeance and victory. This nationalist fervor led to extreme risk-taking and more disaster for the Russians in the East.

The article suggests that this new evidence about Russian overtures for an alliance with Japan calls into question whether or not the Russo-Japanese War was a war of self-defense. While the proverbs that Shiba Ryotaro chose to quote in his books about the conflict might be a bit excessive (for example, “a cornered rat will attack the cat” and “despair makes cowards courageous”), there is little doubt that the Japanese leadership viewed the Russo-Japanese War as a primarily defensive conflict. This is due to both A) the way Meiji Japan and its leadership perceived the international world order and B) the logic of the strategic doctrine Japan followed from the beginning of the Meiji period until well into the 1930s (when it was then replaced with Konoe’s Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere). The historical record on these two points is extremely clear and not likely to be fundamentally altered by a rough draft of a Russian treaty.

To begin, Meiji Japan viewed the international system as a hierarchical one where the ‘strong devour the weak.’ The Ansei Treaties of 1858 was one of the catalysts of the Meiji Restoration and their reversal became the principle foreign policy goal of the Meiji leadership for the next 50 years. After the unequal treaties, Japan was convinced that the only way it could restore its national sovereignty and prestige was to become a great power. During the early 20th century, being a great power meant being an imperial power. Because Japan chose to achieve its modernization through emulation of the West, it promptly set about building an Imperial military capable of projecting it power abroad in emulation of the West as well. The Meiji leaders set out to make Japan a ‘first-rate nation’ (itto koku), which included the prestige and power associated with foreign territorial possession. The Meiji leadership quickly began to relate Japan’s national security with the might of the burgeoning Japanese empire. Japan had its sights set on Korea from the beginning of its empire-building project (the government’s refusal to invade Korea in 1873 even sparked Saigo Takamori’s rebellion, the man many refer to as the ‘last samurai’). Of course the only problem was that a few other countries had their eyes on Korea too – namely, Russia and China.

Enter Yamagata Aritomo, the father of the modern Japanese military and prime minister from 1889-1891 and 1898-1900. In his address to the Diet in 1890, Yamagata requested that a startling 50% of the budget be allocated to the army and navy. In Yamagata’s view, Japan needed to extend its influence beyond its national borders to ensure its own security. He then advanced two strategic principles that would profoundly influence many political and military decisions over the coming decades – the line of sovereignty (Japan’s geographical borders) and the line of advantage (the immediate area beyond the territorial boundary). Yamagata’s speech is as follows:

“The independence and security of the nation depend first on this protection of the line of sovereignty and then the line of advantage…If we wish to maintain the nation’s independence among the powers of the world at the present time, it is not enough to guard only the line of sovereignty; we must also defend the line of advantage…and within the limits of the nation’s resources gradually strive for that position. For this reason, it is necessary to make comparatively large appropriations for our army and navy.”

According to Yamagata, in order to be a totally independent country, it was imperative that Japan both achieved and maintained control over its line of advantage. Yamagata famously referred to Korea as the ‘dagger pointed at the heart of Japan’ that must never fall under foreign domination. In other words, Japan needed to maintain influence over the Korean peninsula due its geographical proximity to the island nation and its borders with Russia and China.

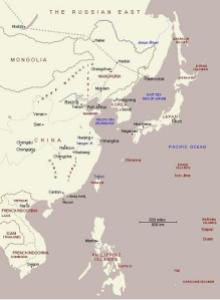

It doesn’t take long to see that the ‘line of advantage’ is flawed by a certain type of circular reasoning. In order to defend Japan’s borders, Japan needed to gain influence and control over Korea. Once Japan secured its influence in Korea, it would then need to maintain control over Manchuria to protect its interests in Korea (especially after the annexation of Korea in 1910). The line of advantage is a line that moves forever outward. First, the line of advantage included Korea. Then, it was extended into Manchuria. It is this strategic logic that triggered both the Sino-Japanese War of 1984-5 and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5. (The line of advantage continued to move outwards, into northern China and eventually encompassed most of East and Southeast Asia. Japan’s involvement in WWI, its conflict with China in 1937 and its leap into war in 1941 were all aimed at securing a line of advantage around Japan that would allow it to be completely autonomous.) Flawed or not, it was with this strategic principle in mind that Japan made many of its decisions during the early 20th century.

In 1890, the problem related to the line of advantage was the situation on the continent. Not only was China attempting to block Japanese interests in Korea, Yamagata feared that the completion of the Siberian railway would give Russia a rapid advance eastwards and the ability to threaten Korea’s ‘independence.’ If Korea’s position changed, Japan’s line of advantage would be endangered. Yamagata’s solution to this was military expansion, then armed conflict. The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-5 allowed Japan to remove the threat of Chinese influence over the government of Korea and secured Japanese interests on the peninsula. Japan also gained a number of valuable territorial possessions, including the Liaodong Peninsula (home of Port Arthur). However, any sense of security this victory afforded Japan was soon lost. In 1895, Germany, Russian, and France forced Japan to give up much of its newly acquired territory, including the Liaodong Peninsula. Russia then signed a 25 year lease on the peninsula and proceeded to set up a naval station at Port Arthur. This Triple Intervention not only increased Japan’s suspicion of Russia’s intentions in the East, but was also a huge blow to Japan’s national pride. According to the logic of imperialism (at least as Japan understood it), territories won in war were completely legitimate. The great powers had never intervened when another Western country increased its empire through armed conflict. The Triple Intervention proved once again that the great powers of the West did not consider Japan as an equal, merely an Asian country whose success was only due to its skillful imitation of the West. Even with the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902, it was quite clear to Japan that, under the guise of the ‘balance of power,’ the great powers were ready to roll back any Japanese acquisition to protect their own interests in Asia. Ultimately, the Triple Intervention had two major effects on Japanese foreign policy; 1) It identified Russia as the number one threat to Japanese imperial ambitions and national security and 2) it reinforced the idea that no matter how successfully Japan conformed to the Western international system, the great powers would never willingly grant it the equality and respect it desired. Both of these developments made Japan more willing to go to war to achieve its foreign policy goals and less likely to respect the wishes of the great powers.

By 1904, the Japanese leadership felt that it was only a matter of time before Russia attempted to draw Korea into its sphere of influence. In addition to the Russian military presence in Port Arthur, which was a security threat to Japan’s line of advantage, the two countries had already spent the last few years arguing over their interests in Manchuria (as well as troop movements during the Boxer Rebellion). Rather than wait for Russia to attack, Japan felt that it was in its own best interest to strike preventively against Russia. By choosing to strike early, under what it perceived as more favorable circumstances, Japan gained an advantage. However, like all war, preventive warfare is a gamble. Even with the advantage of a first strike, Clausewitz’s friction can catch up and result in completely unforeseen consequences and results. All attacks lose momentum over time. The Russo-Japanese War offers a perfect example of this – the Japanese began the war with an enormous advantage over Russia. Their unannounced attack on Port Arthur effectively eliminated the majority of Russia’s Pacific fleet and forced Russia to send its Baltic fleet across a grueling sea voyage before they could continue the naval conflict with Japan. However, a year later both Russia AND Japan had exhausted both their military capabilities and the sympathy of public opinion within their countries. The land war against Russia, a gruesome prologue to the carnage of WWI trench warfare, had whittled away at the Japanese Imperial Army and they had lost all momentum from their victory at Port Arthur.

From the perspective of international law, it is quite clear that the Japanese attack was a preventive, rather than preemptive, strike. There is nothing controversial about preemption. To preempt means to strike first (or attempt to do so) in the face of an attack that is either underway or is very credibly imminent. The decision for war has been taken by the enemy (the classic example of a preemptive war is the Six Day War between Israel and Egypt, Syria and Jordan in 1967).[ii] Because a Russian attack on Japan was definitely not underway on the night of February 8th, it is clear that the Japanese attack on Port Arthur was not a preemptive move.

In contrast, a preventive war is a war of discretion. It differs from preemptive war both in its timing and in its motivation. Unlike the preemptor, who has no choice but to strike, the preventor chooses to wage war “to prevent a predicted enemy from changing the balance of power or otherwise behaving in a manner that the preventor would judge to be intolerable.”[iii] In the case of prevention, the preventor always has a choice. It can choose to tolerate the predicted power shift. It can attempt to lessen the threat through diplomatic or economic means. In the case of prevention, a state chooses war as the best, but not the only, option. Because a preventive war is a war of discretion, it is not as black and white as preemption. How far into the future can a state look when identifying potential enemies? What constitutes a credible threat to a state that would justify preventive action? How certain does must a state be about the possibility of a threat to legitimately strike a preventive blow? What distinguishes a preventive attack from an act of aggression?

According to international law, there are three kinds of war that a state can wage before actually being attacked by the enemy. These terms refer to the temporal distance from an imminent threat – preemption (ex. the Six Day War), prevention (ex. the Russo-Japanese War), and precaution[iv] (say, for example, the Cyclon attack on the 12 Colonies in Battlestar Galactica).[v] Ultimately, there is no legal issue about preventive war: “International law, in the form of the United Nations Charter, recognizes the inherent right of self-defense by states, and it does not oblige a victim state to wait passively to be struck by an aggressor…In short, preventive action by way of anticipatory self-defense is legal, or legal enough.”[vi] Like most matters in international law, it is a matter of interpretation and open to endless debate. Ultimately, however, one must face the fact that the international system is anarchic. Therefore, there is no legal constraint on a state’s right to resort to force. Under this line of reasoning, Japan’s decision to attack Russia in 1904, whether preemptive (which it wasn’t) or preventive (which it was), was perfectly legal under international law. As a sovereign entity, Japan had the sole right to decide what was or wasn’t necessary for its own self-defense. Japan considered Russia’s interference in Manchuria as a threat to its national survival because Manchuria was considered part of Japan’s ‘line of advantage’ – an area in which Japanese interests needed to be protected to ensure national security. Japan acted to protect its vital national interests from an aggressor, and as such international law identifies it as a defensive action. Though the depictions that Japan was beat and goaded into a corner are doubtless overly dramatic, there can be no doubt that the Japanese attack on Port Arthur was, legally speaking, a defensive move.

It is easy to assume a harsh stance towards the actions of imperial Japan during the beginning of the 20th century, especially with the knowledge that many of those actions contributed to the outbreak of two world wars in the Pacific. Most Japanese actions during the early 20th century seem little more than thinly veiled acts of aggression. Hindsight, however, can be the historian’s downfall. Because of the cataclysmic strategic history of the 20th century (with two world wars and the possibility of the third) and the advent of the nuclear age, we now place a moral and political value on peace that simply did not exist in the late 19th to early 20th century. Rather than projecting our 21st century morals onto the events of the past, let’s keep in mind the words of Clausewitz; “War is merely the continuation of policy by other means.” This may not necessarily hold true today, but it certainly did in 1904 when Japan chose to wage a preventative war against Russia. At the beginning of the 20th century, war was considered a perfectly legitimate tool of any imperial state.[vii] Every imperial power has wielded it – Great Britain, Germany, France, Russia, Japan, and, yes, even the United State of America (Spanish-American War, anyone?). Japan saw the protection of its empire as absolutely vital to its survival as a state. As Russia pushed closer to Korea and deeper into Japan’s so-called ‘line of advantage,’ the Japanese became convinced that Russia was a serious threat to its survival as a sovereign nation. In 1854, Britain waged the Crimean War to curb the power and influence of Russia. The Russo-Japanese War was fought for exactly the same reason, so who can deny Japan the legitimacy of its actions?

[i] “Finding Sparks Rethink of Russo-Japanese War.” The Daily Yomiuri.

[ii] Gray, Colin S., The Implications of Preemptive and Preventive War Doctrines: A Reconsideration. Carlisle: Strategic Studies Institute, 2007.

[iii] Gray, v-vi.

[iv] Precautionary war…is war launched to arrest developments beyond the outer temporal or other bounds of detectable current menace. In other words, a precautionary war is a preventive war waged not on the basis of any noteworthy evidence of ill-intent or dangerous capabilities, but rather because those unwelcome phenomena might appear in the future. A precautionary war is a war waged “just in case,” on the basis of the principle, “better safe than sorry.” Gray, 15.

[v] Gray, 7.

[vi] Gray, vi-vii

[vii] But wait! Here a keen observer might interrupt: Even before 1919 and the creation of the League of Nations, there were examples of doctrines differentiating war from other tools of strategy. For one, the just war doctrine of the Catholic Church attempted to maintain a monopoly on the legitimate use of force by outlining six requirements; 1) a just cause, 2) legitimate authority, 3) right intention, 4) proportionality, 5) likelihood of success, and 6) resort to war only as a last resort. While one can question the effectiveness (or even the sincerity) of this document, I must also point out that Japan does not share the same history as the Western world. There is not equivalent of the just war doctrine in Japanese history. Even with the Meiji Restoration and modernization/Westernization of Japan, one can hardly have expected the Japanese to have fully absorbed and accepted Western liberal principles in less than 50 years. Antecedents like the just war doctrine didn’t stop any Western countries from waging imperial wars, so it can hardly be expected to influence Japan.

Tags: critical essay, Japanese history

Recent Comments