危ない義理のできる男色

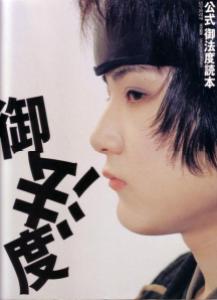

Oshima Nagisa’s 1999 film Gohatto is about desire and suspicion within the ranks of the Shinsengumi during the bakumatsu period. The film can be interpreted as both an examination of the destructive effects of desire within the brotherhood of the militia and as an allegorical criticism of the way modern Japanese society forces individuals to repress their desires for the sake of the group. While the second interpretation is entirely subjective, it is not unlikely given the fact that the director, Oshima Nagisa, commonly uses historical settings to criticize and examine modern society within his films. Furthermore, his failure to accurately reconstruct the sentiments of Tokugawa samurai during the mid-19th century within the film implies that Oshima Nagisa was more interested in using the subject matter to criticize modern society than in accurately reproducing the mentality of the time. It is clear that historical accuracy was not the primary concern of the director. Though Gohatto accurately portrays the environment and the official attitude of Tokugawa lawmakers towards shūdō (male-male relationships), its characters view the subject with an attitude that is far too modern.

Shūdō has a long history in Japan and there is evidence that it has been practiced, to a varying degree, but nearly all social classes. After the establishment of peace by the Tokugawa bakufu, the rise of print and consumer culture (books, woodblock prints, etc.) allowed information about shūdō to be created and disseminated on a scale that had been impossible in earlier, more disruptive times (Pflugfelder , 10). As male-male relationships became more widespread (or at least more well-known) after 1600, the acceptability of shūdō also underwent a transformation. In The Taming of Samurai, Eiko Ikegami states that in the early 1600s, violent fights over beautiful young boys (wakashū) were considered a normal part of samurai life and often considered an acceptable expression of honor. Furthermore, relationships between wakashū and nenja (the older male) sometimes trumped loyalty to one’s lord. As Ikegami elaborates, “During this early stage loyalty and obedience to one’s master had not yet been established as the absolute ethical value. Intimate committed relationships between two individual samurai were sometimes considered more important that the social obligations of hierarchical relationships” (Ikegami, 209). Romantic entanglements can often challenge personal loyalties. Within the film, this potentially subversive force within the Shinsengumi is the love-triangle between Kano Sozaburo, Tashiro Hyozo, and Yuzawa Tojiro.

The Tokugawa bakufu was aware of this disruptive potential within wakashū-nenja relationships and gradually implemented more legislation against the practice of shūdō. Like most legislation passed by the Tokugawa, these restrictions were not always harshly enforced. However, this did allow the Tokugawa to punish such activities when they became socially disruptive. Gregory Pflugfelder makes this point in Cartographies of Desire; “Instead of denying the legitimacy of the “way of youths” altogether, Edo-period lawmakers endeavored, albeit with mixed results, to ensure that the various forms of its pursuit would not conflict with larger political goals and with the maintenance of peace and order in the communities they ruled” [italics mine](Pflugfelder, 19). Similarly in Gohatto, the Shinsengumi leaders are willing to overlook Kano Sozaburo’s relationships as long as they do not become disruptive to the social hierarchy of the group. Oshima Nagisa accurately portrays this attitude and creates the image of an oppressive military environment by displaying the rules of the Shinsengumi (“Code of Conduct”) over a black screen after the first scene of the film. One of the rules is that members of the Shinsengumi are not to engage in private fights or vendettas. Of course, the punishment for violating this rule is disembowelment (seppuku) or beheading. As the bakufu and the Shinsengumi came under increased pressure, both from internal and external threats, they became less likely to tolerate such disruptive behavior. By the mid-19th century, while shūdō was still considered a normal aspect of social life, “it was often considered poor form to make such relationships public because they interfered with the impersonal operations of the bureaucracy”(Ikegami, 291).

Despite its potentially disruptive qualities, shūdō was still considered one of the purest forms of human bonding and the relationship between master and vassal was often metaphorically described in terms of love. This was not necessarily because the master and vassal actually engaged in shūdō, but because the relationship was seen to be based upon “mutual trust, honor, and appreciation of one’s partner’s inner qualities” (Ikegami, 290). In contrast, the characters in Gohatto devote a large amount of their time either denying that they follow ‘that way’ (sono michi) or trying tofigure out if another Shinsengumi member ‘leans that way.’ Given the largely positive connotations associated with shūdō, it is unlikely that they would have been so concerned about such practices. Furthermore, shūdō was not viewed as an ‘either/or’ sexual identity, as we see homosexuality and heterosexuality today, but as one of the several ways of sexuality and interpersonal relationships that an individual could choose follow. In Pflugfelder’s words; “This paradigm…framed male-male sexuality as a “way” (michi or dō) to be pursued and perfected. The rhetoric of Edo-period popular discourse on male-male eroticism was esthetic and ethical…Broadly speaking, we may conceive of a “way” as a discipline of mind and body, a set of practices and knowledge expected to bring both spiritual and physical rewards to those who chose to follow its path” (Pflugfelder, 18 and 28). The characters in Gohatto refer to male-male relations as a ‘way’ but in a modern context – as a sexual identity that is more-or-less fixed.

The character Kano Sozaburo also contains several contradictions. Oshima Nagisa does an excellent job of demonstrating that although Kano is the object of male desire, he is not weak, passive, or overly feminine (despite his looks). He is very skilled in swordsmanship and is quite capable of defending himself from unwanted sexual advances. As Pflugfelder elaborates, a wakashū was found attractive not because of his femininity but because of the beautiful impermanence of his youth. Impending manhood was an aesthetic virtue and the practice of shūdō was seen as a process that helped bring the wakashū into adulthood (Pflugfelder, 35). However, the enigmatic Kano is portrayed as a somewhat malignant force within the Shinsengumi. His motives remain unclear throughout the entire film and it is left ambiguous whether it was he who attacked the other members of the militia. The source of this disruption could potentially be from the fact that Kano refused to follow the proper etiquette of shūdō relations. Though Kano’s sexual partners are left ambiguous, it is clear that he is involved with at least two other members of the Shinsengumi (Tashiro Hyozo and Yuzawa Tojiro) and pursues one with a third. Contrary to the relationships in the film, it is clear that, historically speaking, monogamy was an almost universally accepted principle in wakashū-nenja relationships. According to Pflugfelder, “What we might be tempted to call “monogamy” served as an important, if not universally observed, principle in shūdō ethics – even more so, arguably, than in the sphere of male-female relations”(Pflugfelder, 40). Ikegami also states that “relationships between boys and older lovers should be exclusive and based on mutual trust and fidelity” because the wakashū-nenja relationship was supposed to embody the same loyalty as the lord and his vassal (Ikegami, 290). Kano disregards this component of male-male relationships and as a result members of the Shinsengumi become embroiled in a conflict between who will possess his affection. Though wakashū were seen as the passive party and their desires were usually considered inconsequential, it is clear that Kano has his own desires and is trying, on some level, to see them expressed.

How should the viewer interpret this film? In Visions of the Past: The Challenges of Film to Our Idea of History, Robert Rosenstone asks the reader to examine the intent of history in film (Rosenstone, 51). In other words, why was history used within the film? Does the film use history as drama or history as document? In Gohatto, thedirector may use the lens of history in one of two ways. On one level, the film represents the Shinsengumi as a microcosm of Japan during mid-19th century. The film is set in 1865, the twilight of the Shinsengumi and the Tokugawa bakufu. A year later, a large component of the Shinsengumi will desert the group and in 1868 power will be ‘restored’ to the Meiji emperor. The leaders of the Meiji Restoration will put Japan on a path of ‘modernization’ and many aspects of Japanese life will be abandoned in the pursuit of this goal, including male-male relationships. Captain Hijikata’s cutting of the cherry blossom tree at the end of the film may be symbolic of what Japan needed to sacrifice in order to modernize.

On another level, Gohatto can be seen as a critique of the repressive nature of modern Japanese society and the perceived necessity to stamp out any subversive desires that may threaten the harmony of the group. Oshima Nagisa’s willingness to alter the historical record is evidence that the film is largely preoccupied with modern society and is not overly concerned with accurately presenting history. For example, the iconic teal and white uniform of the Shinsengumi is conspicuously absent and has been replaced by new black and gold uniforms. According to costume designer Emi Wada, the outfits were developed specifically to show a parallel between the Shinsengumi and Hitlerites. Because the attire of the Shinsengumi is well-known and instantly recognizable to the Japanese viewer, redesigning their uniforms was a conscious choice on the part of the director, one that was made to emphasize the eroticism associated with close-knit military environments. This theme is also visually reinforced by the skillfully shot scenes within the Shinsengumi dormitories at night. Men sleep on closely placed futons, legs and covers strewn about, moving restlessly in their sleep. While Gohatto is accurate in representing certain aspects of life in Japan during the mid-19th century, its characters and its meaning are ultimately modern and it contains a message not about the past but about the present. Perhaps it is impossible to separate our view of the past from our modern preoccupations, but as a film Gohatto has more to say about modern society and modern interpretations of sexuality than those of Tokugawa samurai.

Works Cited

Ikegami, Eiko, The Taming of the Samurai: Honorific Individualism and the Making of Modern Japan. Cambridge; Harvard University Press, 1995.

Gohatto. Dir. Oshima Nagisa. BS Asahi, 1999.

Pflugfelder, Gregory M., Cartographies of Desire: Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse, 1600-1950. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rosenstone, Robert A., Visions of the Past: The Challenges of Film to Our Idea of History, Cambridge; Harvard University Press, 1995.

Tags: critical essay, Film Reviews, Japanese culture, Japanese history, Oshima Nagisa

domain

I was extremely pleased to uncover this site. I wanted to thank you

for ones time just for this wonderful read!! I definitely enjoyed every bit of it and i also have

you bookmarked to look at new stuff on your blog.