Yamada Yoji does not make action-packed Hollywood blockbusters. Stemming from the branch of Japanese filmmakers taught by Ozu and Mizoguchi, Yamada’s films usually take a more introspective, down-to-earth direction. While Kabei: Our Mother marks his 80th film, it was only in the early 2000s that Yamada gained the recognition of Western audiences. The films of his samurai trilogy (The Twilight Samurai, The Hidden Blade, and Love and Honor) are all more interested in the internal conflicts of the characters and potent characterizations of the decaying Edo era than in epic, choreographed swordfights. The effect is either lost on the audience or whole-heartedly embraced. In terms of samurai films, Ninja Scroll is a bowl of gyuudon and The Twilight Samurai is kaiseki ryori. Both are delicious, but both are eaten with distinctly different intentions. Additionally, Yamada has built most of his career around depicting two specific eras of Japanese history; the late-Edo (ending in 1867) and Showa (1925-1989). Both of these periods marked times of tremendous change in Japan; the forcible ‘opening’ of Japan to Western trade and end of bakufu (Shogunate) rule (shortly followed by the dissolution of the samurai class) and Japan’s ill-fated foray into imperialism.

Like Yamada’s samurai trilogy, Kabei is not a run-of-the-mill World War II film. The story follows Nogami Kayo (AKA Kabei, played by Yoshinaga Sayuri), a mother who must care for her two daughters after her husband, a professor, is arrested and jailed for expressing opinions contrary to the Imperial war effort. Forced to cope with the difficulties of being a single mother and her own reservations about the rising nationalism in Japan, Kabei raises her daughters with the help of her lovely sister-in-law, a rowdy uncle, and the clumsy and good-hearted Yamasaki. Uninterested in action, Yamada devotes the film’s energy to the portrayal of the characters’ experiences. Uninterested in romanticizing the past, Yamada also places his typical emphasis on historical accuracy and goes to considerable effort to accurately capture the look and atmosphere of Showa era Japan.

The common treatment of the Heian court found in textbooks and survey histories depicts Japan’s ruling class as a group of leisured and effete aristocrats more concerned with composing elaborate waka (poetry) and mastering esoteric Buddhist practices than the effective governance of the country. Furthermore, efforts during the Taika Reform era to adopt a Chinese-style administration and military are dismissed as complete failures, abandoned only a few decades after their inception. As the court “became isolated to an extraordinary degree from the rest of Japanese society,”[1] and could no longer provide an effective military or police system, “provincial residents were forced to take up arms for themselves…[which] allowed the development of large, private warrior networks.”[2] In their respective works, both Karl Friday and William Farris seek to revise this misperception and argue that “the genesis of Japan’s bushi [warrior class] took place within a secure and still-vital imperial state structure.”[3] In Hired Swords: The Rise of Private Warrior Power in Early Japan, Karl Friday traces the evolution of Japan’s military system, from the foundations laid by the Taika Reforms in 645 to Minamoto Yoritomo’s “epoch-making usurpation of power in the 1180s,”[4] to prove it was court activism that concentrated military control in the hands of the rural elite. Furthermore, Friday believes that the court’s growing reliance on the private martial skills of the gentry was motivated by the desire to maximize the efficiency of its military institutions and reflected the changing nature of Japan’s military needs.[5] William Farris advances Friday’s argument in Heavenly Warriors: The Evolution of Japan’s Military, 500-1300 by arguing that the samurai class of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries was the “direct descendant of the mounted archers of yore…[and maintains] that an equestrian mounted elite was a critical factor in society, economy, and politics as early as about A.D. 500.”[6] However, while Farris asserts that the imperial reforms were essential to the evolution of Japan’s mounted military elite, he does not support Friday’s belief that the court successfully took control of the military from the hands of provincial elite. In the context of these two works, the evolution of Japan’s military can be divided into three stages: the centralization of military control and the adoption of Chinese-style mass infantry tactics under the ritsuryō codes during the eighth century, the subsequent ‘abandonment’ of infantry in favor of ‘the privately acquired martial skills of provincial elites and the lower nobility,’[7] and the further organization of private military networks around major provincial warriors during the mid-tenth and eleventh centuries.

The common treatment of the Heian court found in textbooks and survey histories depicts Japan’s ruling class as a group of leisured and effete aristocrats more concerned with composing elaborate waka (poetry) and mastering esoteric Buddhist practices than the effective governance of the country. Furthermore, efforts during the Taika Reform era to adopt a Chinese-style administration and military are dismissed as complete failures, abandoned only a few decades after their inception. As the court “became isolated to an extraordinary degree from the rest of Japanese society,”[1] and could no longer provide an effective military or police system, “provincial residents were forced to take up arms for themselves…[which] allowed the development of large, private warrior networks.”[2] In their respective works, both Karl Friday and William Farris seek to revise this misperception and argue that “the genesis of Japan’s bushi [warrior class] took place within a secure and still-vital imperial state structure.”[3] In Hired Swords: The Rise of Private Warrior Power in Early Japan, Karl Friday traces the evolution of Japan’s military system, from the foundations laid by the Taika Reforms in 645 to Minamoto Yoritomo’s “epoch-making usurpation of power in the 1180s,”[4] to prove it was court activism that concentrated military control in the hands of the rural elite. Furthermore, Friday believes that the court’s growing reliance on the private martial skills of the gentry was motivated by the desire to maximize the efficiency of its military institutions and reflected the changing nature of Japan’s military needs.[5] William Farris advances Friday’s argument in Heavenly Warriors: The Evolution of Japan’s Military, 500-1300 by arguing that the samurai class of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries was the “direct descendant of the mounted archers of yore…[and maintains] that an equestrian mounted elite was a critical factor in society, economy, and politics as early as about A.D. 500.”[6] However, while Farris asserts that the imperial reforms were essential to the evolution of Japan’s mounted military elite, he does not support Friday’s belief that the court successfully took control of the military from the hands of provincial elite. In the context of these two works, the evolution of Japan’s military can be divided into three stages: the centralization of military control and the adoption of Chinese-style mass infantry tactics under the ritsuryō codes during the eighth century, the subsequent ‘abandonment’ of infantry in favor of ‘the privately acquired martial skills of provincial elites and the lower nobility,’[7] and the further organization of private military networks around major provincial warriors during the mid-tenth and eleventh centuries.

Some of you know that I recently went back to America during part of summer vacation. While I was in Los Angeles, my friend Worm (it’s a nickname, don’t ask) was kind enough to take me up to see the Southern Wing of the Commemorative Air Force (CAF) at Camarillo Airport where he volunteers as a pilot. The CAF is a completely volunteer-run non-profit that restores and flies military aircraft – primarily WWII aircraft. Though the United States produced over 300,000 aircraft during the Second World War, almost none remained by 1960. Now, the CAF holds nearly 160 aircraft (60 different types) in various locations across the United States. The fleet includes aircraft from several different countries and aircraft from conflicts since WWII.

The CAF defines their mission as:

The CAF was founded to acquire, restore and preserve in flying condition a complete collection of combat aircraft which were flown by all military services of the United States, and selected aircraft of other nations, for the education and enjoyment of present and future generations of Americans.

More than just a collection of airworthy warplanes from the past, the CAF’s fleet of historic aircraft, known as the CAF Ghost Squadron, recreate, remind and reinforce the lessons learned from the defining moments in American military aviation history.

The CAF travels internationally to hold educational exhibitions and perform air shows. The Southern California Wing of the CAF sports a ridiculously impressive collection of aircraft –

- Grumman F-8F Bearcat, N7825C – Flying

North American SNJ-5 Texan, N89014 – Flying

Grumman F6F-5 Hellcat, N1078Z – Flying

Mitsubishi A6M3 Zero, Model 22, N712Z – Flying

Fairchild PT-19 Cornell, N641BP – Flying

North American SNJ-4 Texan, N6411D – In restoration

Curtiss C-46, China Doll, N53594 – In restoration

North American B-25 Mitchell, N5865V – In restoration

Supermarine Mark XiV Spitfire, N749DP – In restoration

Obviously, I consider the Mitsubishi A6M3 ‘Zero’ to be the crown jewel of their collection. It has been completely restored and it is ONE OF ONLY THREE FLYABLE ZEROS IN THE WORLD. Because Worm is currently being groomed as the Zero’s new pilot, I got to crawl all over the damn thing.

Obviously, I consider the Mitsubishi A6M3 ‘Zero’ to be the crown jewel of their collection. It has been completely restored and it is ONE OF ONLY THREE FLYABLE ZEROS IN THE WORLD. Because Worm is currently being groomed as the Zero’s new pilot, I got to crawl all over the damn thing.

For WWII history buffs, the Zero has acquired an almost mythic reputation. I would argue that its silhouette is THE most recognizable of any WWII aircraft. No one can forget the images of Zeros flying over Pearl Harbor…even if it was a short clip from high school US History class or the images from Michael Bay’s atrocious Pearl Harbor (2001).

Picture Constantine having a history orgasm in the middle of an airstrip in SoCal and you’ll have a good idea of how excited I was.

The Zero was arguably the best carrier-based fighter during WWII, with a maneuverability and range that repeatedly devastated US fighters in dogfights during the early years of the Pacific conflict (especially considering the out-dated equipment that the US was using during 1941). By 1942-1943, however, an improvement in US equipment and tactics undermined the Zero’s ability to hold its own against the US military-industrial machine.

The Model 22 Zero at the SoCal CAF is not the model that was used during the attack on Pearl Harbor. The A6M3 Type 0 Model 22 (零式艦上戦闘機二二型) was produced between December 1942 and summer of 1943. It’s sports a new version of the Model 21’s longer folding wings, a more powerful engine and the longest range of all the Zeros. 560 Model 22s were produced.

To give you an idea of how rare the Zero is – the epic 1970 film Tora! Tora! Tora! (and most film and TV productions) use modified and repainted t-6 Texans. Only one Model 52 was used during the production of Bay’s Pearl Harbor.

Worm and some of the awesome men at the CAF explained to me that the Zero possessed maneuverability, speed and firepower at the expense of protection. There is only one small armor plate behind the cockpit that would do very little to protect the pilot. In contrast, American-built fighters had large amounts of armor plating, which protected the pilots at the expense of weight, maneuverability and speed. Comparing the planes up close, the Zero is absolutely dwarfed by the formidable Grumman F6F-5 Hellcat. One of the pilots ironically described the Zero’s construction as ‘chintzy’ and, indeed, there are large square areas on the Zero’s wings that you must avoid putting any weight on because of the thin metal. But this, too, speaks to the Zero’s efficiency as a carrier-based fighter.

Now for some orgasm worthy pictures (not great quality):

I was also happy to see the P-51 Mustang, complete with a Nazi death count on its side.

I was exceedingly lucky because the CAF were in the process of getting all the WWII aircraft ready for an airshow at a nearby naval base. I therefore got to watch a whole slew of aircraft – including the Zero – take off and fly away in formation. You, readers, are unlucky because I forgot to bring my camera and capture it all on film for you. Better luck next time!

I can honestly say that I would move to LA just to have the opportunity to volunteer at the SoCal CAF and drool over WWII planes (and veterans…and pilots…and Worm) on a regular basis.

For more information:

The CAF Southern California Wing – http://www.cafsocal.com/

The CAF Official Homepage – http://commemorativeairforce.org/

The Second World War is a massive subject, so I will endeavor to stick closely to the subject of The Pacific – the land war fought by the marines in the South Pacific and on the islands surrounding Japan. This will be very difficult for me…those who have had the misfortune of experiencing one of my rants about military history no doubt know that I have a tendency to get a bit overexcited. So, please forgive me for any subsequent deviations from the main theme.

When you think about the Pacific War, you need to think about two things: naval and air power. So much of our modern view of the military application of naval and air power is the product of WWII. When we examine the late 1930s and early 1940s, we need to understand that military thinking was quite different then. For example – the destruction of two-thirds of the Russian fleet at the hands of Admiral Togo in the 1905 Battle of Tsushima convinced nearly every military planner that battleships were going to be the most important and valuable piece of technology for a modern navy. Thus, everyone began building battleships. However, it was not the battleship that proved critical in the war in the Pacific but the aircraft carrier. The development of aviation caused the battleship to get leapfrogged. Nowadays, this seems completely obvious – of course an aircraft carrier’s ability to effectively project military force far exceeds the battleship. However, during the interwar years, military strategists were still unsure of exactly how to use aviation effectively. The Air Force didn’t even exist then, it was still merely a small and little respected division in the Army called the Air Corps (and another division with in the Navy). More importantly, most of the top brass in the Army and Navy remained unconvinced over how effective airpower could be. Yes, it had proved effective during WWI for gathering intelligence or when used in conjunction with land forces such as infantry. Many were skeptical of how effective airpower would be when used alone. This was partially because aviation was still rapidly developing at that time – in the late 1930s, airpower would not have been enough to replace either the navy or coastal artillery in America’s defense, despite Brigadier General William Mitchell’s claim that it could.[1] But it was also due to the revulsion that many felt at the idea of using airpower on civilian targets. You see, it was during WWII, with the aerial bombardments of Britain, Germany, Russia, Japan, China, and almost every single nation associated with the conflict by almost every single nation involved with the conflict, that we began to desensitize ourselves to the questionable morality of bombing densely populated urban areas. In any case, while it is difficult to overemphasis the importance of airpower in the Pacific War, it is also unlikely that many of America’s military planners fully realized this in the late 1930s-early 1940s.

It only takes the opening theme of Band of Brothers to make me cry. Now, I can add The Pacific to that list. I am not embarrassed to admit this, because anyone who is not brought close to tears when they think about World War II is guilty of either the grossest ignorance or the most unforgivable callousness. WWII (I won’t object to adding WWI as well, especially if you adhere to the ‘30 year war’ interpretation) was the most cataclysmic event of the 20th century and, arguably, of mankind’s entire history. And, personally, the Pacific theater of WWII is the closest thing I can think of when I try to imagine Hell.

I spent the majority of the last two years of my undergraduate degree studying WWII, specifically the Pacific theater. I have been reading books about the subject far longer than that. Yet, I have barely scratched the surface. I don’t even dare consider myself an amateur WWII historian; academics devote their entire careers to the subject. But, I know enough about the subject to be able to spot the annoying inaccuracies contained in nearly every movie ever made about the conflict…or to question the way filmmakers choose to portray it.

This is why I have tremendous respect for Steven Spielberg, Tom Hanks, and everyone involved in Band of Brothers and The Pacific. More than attempting to produce cliché-ridden blockbusters that can be peddled off as commodities, they strive to bring historical accuracy and integrity to the filmmaking process. I believe that filmmakers have a personal responsibility to depict WWII as accurately and realistically as possible. And we, as the audience, have a personal responsibility to advance our understanding of the subject past whatever our high school US History class taught us. This applies not only to WWII, but to the subject of WAR in general. War is not cool. It is not glamorous or fun or badass. Even if it is necessary or unavoidable, it is still the single most unimaginably horrible and wasteful act that humans are capable of.

Past the accurate re-creation of battles, uniforms, environment, and technology, past the disturbingly realistic special effects, the makers of Band of Brothers and The Pacific never forget (and never let the audience forget) that they are depicting real events and real people, not fictional characters and exaggerated situations. Put simply, Band of Brothers and The Pacific represent simply some of the finest examples of historical and military filmmaking ever.

I have been anticipating the release of The Pacific for longer than I care to admit. I idolize Stephen Ambrose more than I care to admit. Now that it’s finally coming out, I am going to begin posting my thoughts on the miniseries as it airs.

The Pacific is based on With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa by Eugene B Sledge and Helmet for My Pillow by Robert Leckie. It also draws on the books China Marine by Sledge and Iwo Jima: Red Blood, Black Sand by Chuck Tatum. I have read all of these books and will be comparing them with The Pacific as I post about each episode, with the exception of Iwo Jima: Red Blood, Black Sand. It is currently out of print and since I am no longer near my university library, I won’t be able to reference it. I will also be drawing information from Eagle Against the Sun: The American War With Japan by Ronald Spector, one of the finest and enjoyable pieces of historical scholarship on the Pacific War that I have ever read (despite its obnoxious cover). I highly recommend all of these books to anyone interested in modern history, military history, or WWII.

I hope that the people who read my blog will find these posts interesting and enjoy watching The Pacific as much as I will. The Pacific can be watched online at HBO’s website. As always, I encourage everyone to share their thoughts on the subject as well.

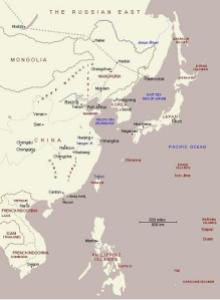

Japanese Imperialism 1894-1945 Review

In the space of 50 years, Japan built an empire that stretched from northern Manchurian down to the tip of Australia. Though its existence proved ephemeral, this was a staggering accomplishment for an island nation that had remained largely (though not completely) disconnected from the Western world until the mid-19th century and had only begun to modernize in 1868. In Japanese Imperialism 1894-1945, W.G. Beasley provides an overview of Japanese territorial expansion and imperialism, beginning with the Sino-Japanese War and ending with Japan’s defeat in the Second World War. In Beasley’s own words, the thesis of this book is as follows; “I do not believe the human impetus towards imperialism needs explaining…What the character of a society, or the international circumstances with which it has to deal, does indeed determine the timing and direction of the impetus, the degree of its success or failure, the kind of advantages that are sought, the institutions that are shaped to give them durability…That is what I propose to examine with respect to Japan” (Beasley, 13). This thesis struck me as vague and somewhat ill-defined. Essentially Beasley does not intended to examine why Japan attempted to carve itself an empire out of East Asia but how it did so. Much of this book is merely a summary of the conventional narrative on the subject with exhaustive references to names and dates. Ultimately, Beasley does not substantially contribute to the historical debate on the subject and merely synthesizes existing lines of thought. Upon turning the last page, the reader knows nothing more than the standard facts and is left to wonder what the point of picking up the book was in the first place.

危ない義理のできる男色

Oshima Nagisa’s 1999 film Gohatto is about desire and suspicion within the ranks of the Shinsengumi during the bakumatsu period. The film can be interpreted as both an examination of the destructive effects of desire within the brotherhood of the militia and as an allegorical criticism of the way modern Japanese society forces individuals to repress their desires for the sake of the group. While the second interpretation is entirely subjective, it is not unlikely given the fact that the director, Oshima Nagisa, commonly uses historical settings to criticize and examine modern society within his films. Furthermore, his failure to accurately reconstruct the sentiments of Tokugawa samurai during the mid-19th century within the film implies that Oshima Nagisa was more interested in using the subject matter to criticize modern society than in accurately reproducing the mentality of the time. It is clear that historical accuracy was not the primary concern of the director. Though Gohatto accurately portrays the environment and the official attitude of Tokugawa lawmakers towards shūdō (male-male relationships), its characters view the subject with an attitude that is far too modern.

A few days ago, I read the article “Finding Sparks Rethink of Russo-Japan War” in the Yomiuri (Link to original article HERE). According to some new documents discovered by University of Tokyo historian Wada Haruki, a key Russian politician attempted to propose an alliance with Japan in the days leading up to the Russo-Japanese War. The article reports that Aleksandr Bezobrazov, a man who has long been considered an advocate of the conflict, first communicated the draft “to Japan’s Foreign Ministry by telegraph on Jan. 1, 1904, by a Japanese diplomat in Russia. The diplomat reported to the ministry in detail about the proposal 12 days later…Despite the tip, Foreign Minister Komura Jutaro met with Prime Minister Katsura Taro, along with the ministers in charge of the army and navy, on Jan. 8, when they agreed to initiate hostilities.”[i] The article concludes that this new finding could lead to a revision of the widely-accepted interpretation that Japan was goaded by Russia into starting the conflict. This may also attract attention in Japan because NHK just started airing a three-year drama series based on a saga by novelist Shiba Ryotaro that depicts the Russo-Japanese War as one of self-defense by Japan.

The fourth episode of my Japanese film series can be found on my YouTube channel. I have also included a critical review of the film.

Shin Heike Monogatari Review

The 1955 film Shin Heike Monogatari follows the Taira clan’s early rise to power. It focuses on the political elements of the consolation of power around the Taira clan as well as the personal relationships between the main characters. Like the original manuscript of the Heike monogatari, the film idealizes the virtues of the samurai and cannot be considered completely accurate. However, despite some romantization, the film ultimately presents a fair depiction of samurai during this period, particularly their comparatively low social standing and the absence of a fully developed sense of a collective group identity.

The second installment of my film series, this time it’s Akira Kurosawa’s 1945 Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail.

Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail Review

Akira Kurosawa’s 1945 film was made and distributed during one of the most pivotal moments of Japanese history. To boost civilian and soldier morale during the Asia-Pacific War, the Japanese Imperial government financed many films that glorified Japan’s feudal past and idealized the sacred bonds of loyalty that supposedly existed between lord and vassal (and by extension the emperor with all Japanese citizens). Akira Kurosawa’s 1945 film Men who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail (Tora no o fumu otokotachi) is no exception. An adaptation of the famous kabuki play Kanjincho, the story revolves around the relationship between Yoshitsune and his loyal vassal Benkei, a warrior-monk. Though the film was initially criticized as being too democratic by the Imperial government before Japan’s surrender, it was banned by the American Occupation for it’s “feudalistic idea of loyalty” and was not released until 1952. With the exception of an additional porter, who adds a very Western-style comic relief to the film, Kurosawa’s adaptation is almost a straight reproduction of the kabuki play.[1] Therefore, the film contains both a representation of Tokugawa-era sentiments as well as the ideology of the 1940s.

Recent Comments