Horror is typically regarded as the least feminist genre of film; a genre that routinely objectifies, sexualizes, tortures, rapes and murders women and girls. However, if viewed from a different angle, horror films often feature story lines that grant wronged women the power and agency (in death) to respond to the injustices done to them in life.

‘Dead wet girls’ is a term coined by David Kalat in his book J-Horror to describe the unique female ghosts who are so iconic in Japanese horror. While popular Japanese films like RING and JU-ON have made this figure recognizable to Western audience, the wronged woman has been a prominent figure in Japanese ghost stories and mythology for centuries. Of course, the interpretation of these stories is fairly ambivalent; often the presence of malignant ghosts and spirits is connected back to the failure of mothers and wives to perform their womanly duties. In many Japanese folktales, female spirits are connected back to the savage and unpredictable natural world.

TRADITIONAL JAPANESE GHOST TALES

The best example of this connection to nature is the Yuki-onna (snow woman), famously depicted in Kobayashi Masaki’s KWAIDAN (1964). The Yuki-onna is a beautiful woman with long black hair, who typically appears before travelers lost in snow. The Yuki-onna typically kills the unfortunate travelers she meets, though she may also take unsuspecting men as lovers in a succubus-like fashion. She is essentially the manifestation of winter; beautiful and serene yet capable of ruthlessly killing those who are ill-prepared. She is also a reminder of a woman’s fury – like nature, no woman can ever be fully trusted. Kobayashi Masaki’s depiction of the Yuki-onna is captivatingly surreal. Starring Nakadai Tatsuya, the entire segment was filmed in an obviously artificial indoor set with swirling painted backgrounds (featuring an ominous eye).

Already before Perfect Blue I wrote a script for another director [Katsuhiro Otomo], an episode of the omnibus film Memories called Magnetic Rose. It was also a story of confusion between memory and the real world. Because I didn’t direct it myself I was a bit concerned about how it was turning out. On many occasions I thought I would have done things differently. I got my chance to realize those thoughts with Perfect Blue. So I already had an interest in that kind of plot, to consciously compose the story in such a manner… To be honest, I care very little about the idea of the stalker in Perfect Blue. The storytelling aspects interest me much more. Looking at things objectively or subjectively gives two very different images. For an outsider, the dreams and the film within a film are easy to separate from the real world. But for the person who is experiencing them, everything is real. I wanted to describe that kind of situation, so I applied it in Perfect Blue. [Kon Satoshi, Midnight Eye Interview]

While all of Kon Satoshi’s work explores similar themes, the thematic line that runs through Magnetic Rose, Perfect Blue, and Millennium Actress (his first three works) is the strongest and easiest to identify. All three films are stories about the confusion between reality and fantasy, the subjective nature of perception and memory, and the identity of the female performer. While Kon explored many of these themes within the script for Magnetic Rose (which I discussed in the previous post), he was finally able to take the helm as director in the 1998 Perfect Blue. The result is an astounding cinematic tour de force. In her essay “‘Excuse Me, Who Are You?’: Performance, the Gaze and the Female in the Works of Kon Satoshi” from Cinema Anime, Susan Napier elaborates, “I use the term tour de force because the film’s brilliant use of animation and unreality creates a unique viewing experience, forcing the viewer to question not only the protagonist’s perceptions but his or her own as he/she follows the protagonist into a surreal world of madness and illusion” (33). For this essay, I would like to examine the themes Kon addresses within Perfect Blue as well as the formal and narrative techniques that he employs to express them. Finally, I will conclude with a discussion of the film’s ending and interpretations.

Unlike the West, Japan does not have a history of strong feminist movements – or, at least, Japanese feminism is less focused on individual autonomy than Western feminism. Even today, most ‘feminist’ dialogue takes place within community or civil rights organizations, not feminist activist groups. While the position of women within Japanese society has changed since the 1985 Equal Employment Opportunity Law (EEOL, AKA ‘Japan’s Toothless Lion’) passed, Japan is still a country characterized by an M-shaped labor curve for women and abortion is still a preferred form of birth control, due both to cultural factors and the difficulty and expense associated with using oral contraceptives. I would also like to point out that many observers believe that low-dose oral contraceptives were finally approved for use in Japan in late 1999 (after 35 years of debate) because that the Diet fast-tracked the approval of Viagra (which took about 6 months). Therefore, one must ask: how successful has women’s suffrage been within Japanese society?

Magnetic Rose (a rather loose translation of 彼女の想いで, “her memories”) is the first of three episodes based on the manga short stories of Otomo Katsuhiro (the genius behind Akira). Directed by Morimoto Koji, Magnetic Rose does not offer any insight into Kon Satoshi’s work as a director. However, he wrote the adaption of Otomo’s original manga story and the episode contains many of the key themes that Kon explores in his later work. Specifically, Magnetic Rose explores the boundary between reality and illusion, the role of perception and memory, and femininity.

Magnetic Rose (a rather loose translation of 彼女の想いで, “her memories”) is the first of three episodes based on the manga short stories of Otomo Katsuhiro (the genius behind Akira). Directed by Morimoto Koji, Magnetic Rose does not offer any insight into Kon Satoshi’s work as a director. However, he wrote the adaption of Otomo’s original manga story and the episode contains many of the key themes that Kon explores in his later work. Specifically, Magnetic Rose explores the boundary between reality and illusion, the role of perception and memory, and femininity.

Drawing inspiration from the story and music of Madame Butterfly and 2001: A Space Odyssey, Magnetic Rose follows the members of the deep space salvage vessel Corona. While performing a salvage mission, the crew encounters an odd distress signal emanating from the Sargasso region, ominously nicknamed ‘the graveyard of space.’ Each man has their own reasons for working in deep space, namely to ‘build houses in California.’ Specifically, Miguel is looking forward to being united with one of his beautiful girlfriends and Heinz longs to return to his family.

Drawing inspiration from the story and music of Madame Butterfly and 2001: A Space Odyssey, Magnetic Rose follows the members of the deep space salvage vessel Corona. While performing a salvage mission, the crew encounters an odd distress signal emanating from the Sargasso region, ominously nicknamed ‘the graveyard of space.’ Each man has their own reasons for working in deep space, namely to ‘build houses in California.’ Specifically, Miguel is looking forward to being united with one of his beautiful girlfriends and Heinz longs to return to his family.

The crew discovers a destroyed space station and Heinz and Miguel are sent in to investigate. Once onboard, Heinz and Miguel are lured deeper into the baroque interior of the space station, following various holographic images of the beautiful Eva Friedel. A famous opera singer, Eva fell from grace after she lost her voice and disappeared completely after the murder of her fiancée, Carlo. As the two men venture deeper into the ship, the holograms begin to reflect their own dreams and memories and the difference between illusion and reality become increasingly difficult to distinguish.

Though the narrative is about the two men, the story actually revolves around the feminine presence. It is the figures of Eva Friedel and Heintz’s daughter Emily who stand, in the words of Susan Napier, “at the nexus point between real and unreal, ultimately beckoning the men towards death” [1]. The recurring images of roses and the haunting strains of Madame Butterfly are very powerful feminine symbols. Simultaneously alluring and sinister, Eva seduces Miguel into believing he is her fiancée. However, it turns out that it was actually Eva who murdered Carlo because he broke off their engagement. According to Eva, “Carlo lives forever. With me, in my memories…In my memories he will never change his mind.” This is, in fact, Eva’s own attempt to manipulate her own memory into reality.

Though the narrative is about the two men, the story actually revolves around the feminine presence. It is the figures of Eva Friedel and Heintz’s daughter Emily who stand, in the words of Susan Napier, “at the nexus point between real and unreal, ultimately beckoning the men towards death” [1]. The recurring images of roses and the haunting strains of Madame Butterfly are very powerful feminine symbols. Simultaneously alluring and sinister, Eva seduces Miguel into believing he is her fiancée. However, it turns out that it was actually Eva who murdered Carlo because he broke off their engagement. According to Eva, “Carlo lives forever. With me, in my memories…In my memories he will never change his mind.” This is, in fact, Eva’s own attempt to manipulate her own memory into reality.

Meanwhile, Eva similarly attempts to seduce Heinz with the image of his daughter Emily. At the beginning of the episode, the viewer is led to believe that Heinz is waiting to return home to his family. However, we ultimately discover that his daughter is dead and the photograph in his wallet only a memory. Though Heinz refuses to accept the hologram as reality, proclaiming “Memories aren’t an escape!”, this realization comes too late. The Corona and its crew are destroyed in the blast generated to break away from Eva’s ship and Heinz is sucked out into space. In the final frame of the film, Heinz is drifting away from the rose-shaped wreckage, holographic rose petals floating in his helmet.

Meanwhile, Eva similarly attempts to seduce Heinz with the image of his daughter Emily. At the beginning of the episode, the viewer is led to believe that Heinz is waiting to return home to his family. However, we ultimately discover that his daughter is dead and the photograph in his wallet only a memory. Though Heinz refuses to accept the hologram as reality, proclaiming “Memories aren’t an escape!”, this realization comes too late. The Corona and its crew are destroyed in the blast generated to break away from Eva’s ship and Heinz is sucked out into space. In the final frame of the film, Heinz is drifting away from the rose-shaped wreckage, holographic rose petals floating in his helmet.

Throughout Magnetic Rose, both men are motivated by their desires – for Miguel, the desire for the mysterious Eva, and for Heinz the desire to be reunited with his daughter. Because both desires only lead to destruction, the viewer is left with ‘a sense of the emptiness of desire’ [2]. Furthermore, the fact that both of these desires are impossible to attain – both Eva and Heinz’s daughter are dead – speak to the inherent danger of memory and nostalgia.

Magnetic Rose contains several themes that Kon Satoshi moves on to explore in his later work; reality and illusion, as represented by the holograms, and memory and nostalgia, as represented by Heinz’s daughter. However, the character of Eva Friedel contains the clearest link between Magnetic Rose and Kon’s later work. More than an embittered woman, Eva herself was a victim. An opera singer, Eva lost everything – the admiration of her fans and the love of her fiancée – when she lost her voice. His murder and Eva’s subsequent retreat into the space station represent both an act of vengeance and an attempt to preserve the memory of her former glory. In particular, the numerous images of Eva that cover the interior of the ship, old news clippings, and the holographic representations of her fans have a strong connection to Kon’s next project Perfect Blue.

Magnetic Rose contains several themes that Kon Satoshi moves on to explore in his later work; reality and illusion, as represented by the holograms, and memory and nostalgia, as represented by Heinz’s daughter. However, the character of Eva Friedel contains the clearest link between Magnetic Rose and Kon’s later work. More than an embittered woman, Eva herself was a victim. An opera singer, Eva lost everything – the admiration of her fans and the love of her fiancée – when she lost her voice. His murder and Eva’s subsequent retreat into the space station represent both an act of vengeance and an attempt to preserve the memory of her former glory. In particular, the numerous images of Eva that cover the interior of the ship, old news clippings, and the holographic representations of her fans have a strong connection to Kon’s next project Perfect Blue.

For me, Magnetic Rose does fall prey to one of the more amusing characteristics of anime. The names and characterization of the characters are quite ridiculous. The name of the ship, Corona, makes me think of the beer and the characters sport names like Ivanov and Miguel (you know, to represent how international the crew is). Heinz is the best example of this. His blonde hair, blue eyes, and hulky build identify him as foreign. When we are transported into his memory of home, German music plays in the background. Clearly, with a name like Heinz, he must be German (or a member of the ketchup dynasty).

Joking aside, Magnetic Rose alone represents a strong addition to the anime genre. The animation and mecha designs are top notch and the story is absolutely fantastic. It is also a short and easy introduction to Kon Satoshi. Highly recommended.

Coming up next is Perfect Blue.

Works Cited

Napier, Susan J. “‘Excuse Me, Who Are You?’: Performance, the Gaze, and the Female in the Works of Kon Satoshi,” Cinema Anime: Critical Engagements With Japanese Animation. Ed. Steven T. Brown. New York: Palgrave Macmillian, 2006.

If you go to Japan or have Japanese friends you’re bound to run into a purikura photo or photo booth. Purikura stands for purinto kurabu (プリント倶楽部), or print club. These photo booths were introduced in 1995 and by 1997 over 45,000 booths existed around the country (Okabe, Daisuke et al., pg. 1). It is popular with girls from the ages or 15 to 20. Virtually every Japanese high school girl take purikura photos and purikura is used as a way to visually display friendships and social networks to other (Okabe, Daisuke et al., pg. 2). Purikura are large photo booths that can hold anywhere from 4 to 8 people and offer a variety of background options for the users. After the photo has been taken, the girls can then go to a modification screen and write various kinds of ‘graffiti’ on their photos. They can also add image modifications to the photos, like makeup, different hairstyles, etc. The finished photos are printed out on sheets of self-adhesive stickers. Girls collect their purikura in photo albums as a sort of diary and carry the extra photos in a small container they call ‘puri-cans.’ High school girls look at their purikura albums with each other all the time, during lunchtime, after school, even in class. My students have given me purikura photos of themselves and their friends. Girls also exchange purikura photos with their friends. While some girls bring their boyfriends into purikura booths with them occasionally, the activity is mainly for girls (a Japanese boy would not own a purikura album).

危ない義理のできる男色

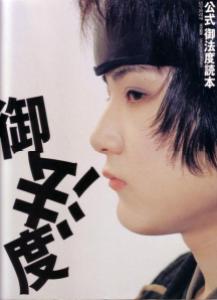

Oshima Nagisa’s 1999 film Gohatto is about desire and suspicion within the ranks of the Shinsengumi during the bakumatsu period. The film can be interpreted as both an examination of the destructive effects of desire within the brotherhood of the militia and as an allegorical criticism of the way modern Japanese society forces individuals to repress their desires for the sake of the group. While the second interpretation is entirely subjective, it is not unlikely given the fact that the director, Oshima Nagisa, commonly uses historical settings to criticize and examine modern society within his films. Furthermore, his failure to accurately reconstruct the sentiments of Tokugawa samurai during the mid-19th century within the film implies that Oshima Nagisa was more interested in using the subject matter to criticize modern society than in accurately reproducing the mentality of the time. It is clear that historical accuracy was not the primary concern of the director. Though Gohatto accurately portrays the environment and the official attitude of Tokugawa lawmakers towards shūdō (male-male relationships), its characters view the subject with an attitude that is far too modern.

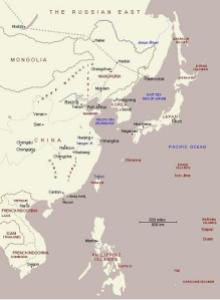

A few days ago, I read the article “Finding Sparks Rethink of Russo-Japan War” in the Yomiuri (Link to original article HERE). According to some new documents discovered by University of Tokyo historian Wada Haruki, a key Russian politician attempted to propose an alliance with Japan in the days leading up to the Russo-Japanese War. The article reports that Aleksandr Bezobrazov, a man who has long been considered an advocate of the conflict, first communicated the draft “to Japan’s Foreign Ministry by telegraph on Jan. 1, 1904, by a Japanese diplomat in Russia. The diplomat reported to the ministry in detail about the proposal 12 days later…Despite the tip, Foreign Minister Komura Jutaro met with Prime Minister Katsura Taro, along with the ministers in charge of the army and navy, on Jan. 8, when they agreed to initiate hostilities.”[i] The article concludes that this new finding could lead to a revision of the widely-accepted interpretation that Japan was goaded by Russia into starting the conflict. This may also attract attention in Japan because NHK just started airing a three-year drama series based on a saga by novelist Shiba Ryotaro that depicts the Russo-Japanese War as one of self-defense by Japan.

Recent Comments