The common treatment of the Heian court found in textbooks and survey histories depicts Japan’s ruling class as a group of leisured and effete aristocrats more concerned with composing elaborate waka (poetry) and mastering esoteric Buddhist practices than the effective governance of the country. Furthermore, efforts during the Taika Reform era to adopt a Chinese-style administration and military are dismissed as complete failures, abandoned only a few decades after their inception. As the court “became isolated to an extraordinary degree from the rest of Japanese society,”[1] and could no longer provide an effective military or police system, “provincial residents were forced to take up arms for themselves…[which] allowed the development of large, private warrior networks.”[2] In their respective works, both Karl Friday and William Farris seek to revise this misperception and argue that “the genesis of Japan’s bushi [warrior class] took place within a secure and still-vital imperial state structure.”[3] In Hired Swords: The Rise of Private Warrior Power in Early Japan, Karl Friday traces the evolution of Japan’s military system, from the foundations laid by the Taika Reforms in 645 to Minamoto Yoritomo’s “epoch-making usurpation of power in the 1180s,”[4] to prove it was court activism that concentrated military control in the hands of the rural elite. Furthermore, Friday believes that the court’s growing reliance on the private martial skills of the gentry was motivated by the desire to maximize the efficiency of its military institutions and reflected the changing nature of Japan’s military needs.[5] William Farris advances Friday’s argument in Heavenly Warriors: The Evolution of Japan’s Military, 500-1300 by arguing that the samurai class of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries was the “direct descendant of the mounted archers of yore…[and maintains] that an equestrian mounted elite was a critical factor in society, economy, and politics as early as about A.D. 500.”[6] However, while Farris asserts that the imperial reforms were essential to the evolution of Japan’s mounted military elite, he does not support Friday’s belief that the court successfully took control of the military from the hands of provincial elite. In the context of these two works, the evolution of Japan’s military can be divided into three stages: the centralization of military control and the adoption of Chinese-style mass infantry tactics under the ritsuryō codes during the eighth century, the subsequent ‘abandonment’ of infantry in favor of ‘the privately acquired martial skills of provincial elites and the lower nobility,’[7] and the further organization of private military networks around major provincial warriors during the mid-tenth and eleventh centuries.

The common treatment of the Heian court found in textbooks and survey histories depicts Japan’s ruling class as a group of leisured and effete aristocrats more concerned with composing elaborate waka (poetry) and mastering esoteric Buddhist practices than the effective governance of the country. Furthermore, efforts during the Taika Reform era to adopt a Chinese-style administration and military are dismissed as complete failures, abandoned only a few decades after their inception. As the court “became isolated to an extraordinary degree from the rest of Japanese society,”[1] and could no longer provide an effective military or police system, “provincial residents were forced to take up arms for themselves…[which] allowed the development of large, private warrior networks.”[2] In their respective works, both Karl Friday and William Farris seek to revise this misperception and argue that “the genesis of Japan’s bushi [warrior class] took place within a secure and still-vital imperial state structure.”[3] In Hired Swords: The Rise of Private Warrior Power in Early Japan, Karl Friday traces the evolution of Japan’s military system, from the foundations laid by the Taika Reforms in 645 to Minamoto Yoritomo’s “epoch-making usurpation of power in the 1180s,”[4] to prove it was court activism that concentrated military control in the hands of the rural elite. Furthermore, Friday believes that the court’s growing reliance on the private martial skills of the gentry was motivated by the desire to maximize the efficiency of its military institutions and reflected the changing nature of Japan’s military needs.[5] William Farris advances Friday’s argument in Heavenly Warriors: The Evolution of Japan’s Military, 500-1300 by arguing that the samurai class of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries was the “direct descendant of the mounted archers of yore…[and maintains] that an equestrian mounted elite was a critical factor in society, economy, and politics as early as about A.D. 500.”[6] However, while Farris asserts that the imperial reforms were essential to the evolution of Japan’s mounted military elite, he does not support Friday’s belief that the court successfully took control of the military from the hands of provincial elite. In the context of these two works, the evolution of Japan’s military can be divided into three stages: the centralization of military control and the adoption of Chinese-style mass infantry tactics under the ritsuryō codes during the eighth century, the subsequent ‘abandonment’ of infantry in favor of ‘the privately acquired martial skills of provincial elites and the lower nobility,’[7] and the further organization of private military networks around major provincial warriors during the mid-tenth and eleventh centuries.

Some of you know that I recently went back to America during part of summer vacation. While I was in Los Angeles, my friend Worm (it’s a nickname, don’t ask) was kind enough to take me up to see the Southern Wing of the Commemorative Air Force (CAF) at Camarillo Airport where he volunteers as a pilot. The CAF is a completely volunteer-run non-profit that restores and flies military aircraft – primarily WWII aircraft. Though the United States produced over 300,000 aircraft during the Second World War, almost none remained by 1960. Now, the CAF holds nearly 160 aircraft (60 different types) in various locations across the United States. The fleet includes aircraft from several different countries and aircraft from conflicts since WWII.

The CAF defines their mission as:

The CAF was founded to acquire, restore and preserve in flying condition a complete collection of combat aircraft which were flown by all military services of the United States, and selected aircraft of other nations, for the education and enjoyment of present and future generations of Americans.

More than just a collection of airworthy warplanes from the past, the CAF’s fleet of historic aircraft, known as the CAF Ghost Squadron, recreate, remind and reinforce the lessons learned from the defining moments in American military aviation history.

The CAF travels internationally to hold educational exhibitions and perform air shows. The Southern California Wing of the CAF sports a ridiculously impressive collection of aircraft –

- Grumman F-8F Bearcat, N7825C – Flying

North American SNJ-5 Texan, N89014 – Flying

Grumman F6F-5 Hellcat, N1078Z – Flying

Mitsubishi A6M3 Zero, Model 22, N712Z – Flying

Fairchild PT-19 Cornell, N641BP – Flying

North American SNJ-4 Texan, N6411D – In restoration

Curtiss C-46, China Doll, N53594 – In restoration

North American B-25 Mitchell, N5865V – In restoration

Supermarine Mark XiV Spitfire, N749DP – In restoration

Obviously, I consider the Mitsubishi A6M3 ‘Zero’ to be the crown jewel of their collection. It has been completely restored and it is ONE OF ONLY THREE FLYABLE ZEROS IN THE WORLD. Because Worm is currently being groomed as the Zero’s new pilot, I got to crawl all over the damn thing.

Obviously, I consider the Mitsubishi A6M3 ‘Zero’ to be the crown jewel of their collection. It has been completely restored and it is ONE OF ONLY THREE FLYABLE ZEROS IN THE WORLD. Because Worm is currently being groomed as the Zero’s new pilot, I got to crawl all over the damn thing.

For WWII history buffs, the Zero has acquired an almost mythic reputation. I would argue that its silhouette is THE most recognizable of any WWII aircraft. No one can forget the images of Zeros flying over Pearl Harbor…even if it was a short clip from high school US History class or the images from Michael Bay’s atrocious Pearl Harbor (2001).

Picture Constantine having a history orgasm in the middle of an airstrip in SoCal and you’ll have a good idea of how excited I was.

The Zero was arguably the best carrier-based fighter during WWII, with a maneuverability and range that repeatedly devastated US fighters in dogfights during the early years of the Pacific conflict (especially considering the out-dated equipment that the US was using during 1941). By 1942-1943, however, an improvement in US equipment and tactics undermined the Zero’s ability to hold its own against the US military-industrial machine.

The Model 22 Zero at the SoCal CAF is not the model that was used during the attack on Pearl Harbor. The A6M3 Type 0 Model 22 (零式艦上戦闘機二二型) was produced between December 1942 and summer of 1943. It’s sports a new version of the Model 21’s longer folding wings, a more powerful engine and the longest range of all the Zeros. 560 Model 22s were produced.

To give you an idea of how rare the Zero is – the epic 1970 film Tora! Tora! Tora! (and most film and TV productions) use modified and repainted t-6 Texans. Only one Model 52 was used during the production of Bay’s Pearl Harbor.

Worm and some of the awesome men at the CAF explained to me that the Zero possessed maneuverability, speed and firepower at the expense of protection. There is only one small armor plate behind the cockpit that would do very little to protect the pilot. In contrast, American-built fighters had large amounts of armor plating, which protected the pilots at the expense of weight, maneuverability and speed. Comparing the planes up close, the Zero is absolutely dwarfed by the formidable Grumman F6F-5 Hellcat. One of the pilots ironically described the Zero’s construction as ‘chintzy’ and, indeed, there are large square areas on the Zero’s wings that you must avoid putting any weight on because of the thin metal. But this, too, speaks to the Zero’s efficiency as a carrier-based fighter.

Now for some orgasm worthy pictures (not great quality):

I was also happy to see the P-51 Mustang, complete with a Nazi death count on its side.

I was exceedingly lucky because the CAF were in the process of getting all the WWII aircraft ready for an airshow at a nearby naval base. I therefore got to watch a whole slew of aircraft – including the Zero – take off and fly away in formation. You, readers, are unlucky because I forgot to bring my camera and capture it all on film for you. Better luck next time!

I can honestly say that I would move to LA just to have the opportunity to volunteer at the SoCal CAF and drool over WWII planes (and veterans…and pilots…and Worm) on a regular basis.

For more information:

The CAF Southern California Wing – http://www.cafsocal.com/

The CAF Official Homepage – http://commemorativeairforce.org/

Back in April/May, my mother came to visit me in Japan. During our trip down to Osaka, we took a ‘little’ detour into the nearby Wakayama-ken. Our destination: Koyasan (高野山). Founded in 819 by the monk Kukai (AKA Kobo Daishi), Koyasan is the world headquarters of the Koyasan Shingon sect of Buddhism. Home to approximately 120 temples, Koyasan is definitely a place where monks outnumber lay-people.

Back in April/May, my mother came to visit me in Japan. During our trip down to Osaka, we took a ‘little’ detour into the nearby Wakayama-ken. Our destination: Koyasan (高野山). Founded in 819 by the monk Kukai (AKA Kobo Daishi), Koyasan is the world headquarters of the Koyasan Shingon sect of Buddhism. Home to approximately 120 temples, Koyasan is definitely a place where monks outnumber lay-people.

My mother is fascinated with monks and Japanese Buddhism, so Koyasan was a definite MUST during her trip. For her, I think both fall clearly into the ‘Oriental Mystique’ category. Personally, my image of monks is based almost entirely on my knowledge of the Heian period of Japanese history. Specifically, when I think ‘monk’ I think of two things – the Heike Monogatari and The Teeth and Claws of the Buddha by Mikael Adolphson. The Heian period ended in 1185 and ‘sohei’ (warrior monks) have pretty much been extinct since Nobunaga set fire to Enryaku-ji back in 1571, so it’s safe to say that my knowledge of monks is a bit outdated. What can I say, I love living in the past.

Despite our combined ignorance, we were both interested in doing a ‘temple stay’ – where you stay in one of the local Buddhism temples and can enjoy some shojin ryori or ‘devotion food.’ (It’s all vegetarian, of course.) Little did we know that our trip to Koyasan would coincide with one of their most important ceremonies – the Kenchien Kanjo.

After we settled into our room at the Sekisho-in, some friendly monks ushered us out the door and ordered us to immediately head to the Garan. We followed a mass of Buddhist pilgrims clad in white and weilding votive candles down a gravel path illuminated by lanterns. The tree-lined path opened up to reveal an impressive orange-and-white pagoda. While monks bustled back and forth, the spring air was filled with chanting.

After we settled into our room at the Sekisho-in, some friendly monks ushered us out the door and ordered us to immediately head to the Garan. We followed a mass of Buddhist pilgrims clad in white and weilding votive candles down a gravel path illuminated by lanterns. The tree-lined path opened up to reveal an impressive orange-and-white pagoda. While monks bustled back and forth, the spring air was filled with chanting.

Further up the path lay the Kondo, a massive wooden structure that was originally built by Kobo Daishi in 819 (it has subsequently been rebuilt 7 times, probably due to fires).

The Kechien Kanjo is a Buddhist ritual where the blindfolded participant throws a flower into the Taizokai (Womb of the World Mandala) to establish a link between the participant and one of the emanation forms of Dainichi Nyorai. Afterward, water is used to wash away all worldly desires. On the first day, a procession of monks in colorful brocade robes called the Teigi Dai-Mandala0ku is held.

Day One in Koyasan –

Day Two:

How to Get There:

From Osaka’s NAMBA STATION take the NANKAI KOYA LINE to GOKURAKUBASHI STATION. From there, board the cable car for a brief ride to KOYASAN STATION at the top of the mountain. From Koyasan station, take the bus (there’s only one) to the town center.

Nankai Railways actually offers a KOYASAN WORLD HERITAGE ticket. This pass includes a round trip ticket to Koyasan from Namba Station, unlimited travel on the buses in Koyasan, and discount admission to certain attractions in Koyasan. The pass is valid for two consecutive days. The Regular version will cost you 2,780 per person and the Limited Express version is 3,310 per person.

Following the model laid out by Band of Brothers, The Pacific begins with actual footage of Pearl Harbor and interviews with some of the veterans of the Pacific War. We’re rapidly approaching the time when the generation who fought in WWII will be gone and I find these interviews extremely valuable. In Band of Brothers, they were often the most heart-wrenching parts of each episode. I am immensely happy that The Pacific has continued using real footage and interviews – it reminds the audience that this show is based in fact and reality.

As I mentioned earlier, the United States was not ready to go to war with Japan on December 7th, 1941. While the American military had been anticipating a war with Japan for some time, they did not have the equipment or men needed to engage in a massive war halfway around the world. On August 7th, 1942, eight months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Guadalcanal became the first major offensive of the Pacific War precisely because the United States needed to spend that time training soldiers (marines specifically) to fight the Japanese in the South Pacific.

It only takes the opening theme of Band of Brothers to make me cry. Now, I can add The Pacific to that list. I am not embarrassed to admit this, because anyone who is not brought close to tears when they think about World War II is guilty of either the grossest ignorance or the most unforgivable callousness. WWII (I won’t object to adding WWI as well, especially if you adhere to the ‘30 year war’ interpretation) was the most cataclysmic event of the 20th century and, arguably, of mankind’s entire history. And, personally, the Pacific theater of WWII is the closest thing I can think of when I try to imagine Hell.

I spent the majority of the last two years of my undergraduate degree studying WWII, specifically the Pacific theater. I have been reading books about the subject far longer than that. Yet, I have barely scratched the surface. I don’t even dare consider myself an amateur WWII historian; academics devote their entire careers to the subject. But, I know enough about the subject to be able to spot the annoying inaccuracies contained in nearly every movie ever made about the conflict…or to question the way filmmakers choose to portray it.

This is why I have tremendous respect for Steven Spielberg, Tom Hanks, and everyone involved in Band of Brothers and The Pacific. More than attempting to produce cliché-ridden blockbusters that can be peddled off as commodities, they strive to bring historical accuracy and integrity to the filmmaking process. I believe that filmmakers have a personal responsibility to depict WWII as accurately and realistically as possible. And we, as the audience, have a personal responsibility to advance our understanding of the subject past whatever our high school US History class taught us. This applies not only to WWII, but to the subject of WAR in general. War is not cool. It is not glamorous or fun or badass. Even if it is necessary or unavoidable, it is still the single most unimaginably horrible and wasteful act that humans are capable of.

Past the accurate re-creation of battles, uniforms, environment, and technology, past the disturbingly realistic special effects, the makers of Band of Brothers and The Pacific never forget (and never let the audience forget) that they are depicting real events and real people, not fictional characters and exaggerated situations. Put simply, Band of Brothers and The Pacific represent simply some of the finest examples of historical and military filmmaking ever.

I have been anticipating the release of The Pacific for longer than I care to admit. I idolize Stephen Ambrose more than I care to admit. Now that it’s finally coming out, I am going to begin posting my thoughts on the miniseries as it airs.

The Pacific is based on With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa by Eugene B Sledge and Helmet for My Pillow by Robert Leckie. It also draws on the books China Marine by Sledge and Iwo Jima: Red Blood, Black Sand by Chuck Tatum. I have read all of these books and will be comparing them with The Pacific as I post about each episode, with the exception of Iwo Jima: Red Blood, Black Sand. It is currently out of print and since I am no longer near my university library, I won’t be able to reference it. I will also be drawing information from Eagle Against the Sun: The American War With Japan by Ronald Spector, one of the finest and enjoyable pieces of historical scholarship on the Pacific War that I have ever read (despite its obnoxious cover). I highly recommend all of these books to anyone interested in modern history, military history, or WWII.

I hope that the people who read my blog will find these posts interesting and enjoy watching The Pacific as much as I will. The Pacific can be watched online at HBO’s website. As always, I encourage everyone to share their thoughts on the subject as well.

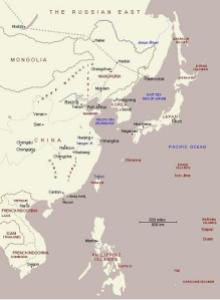

Japanese Imperialism 1894-1945 Review

In the space of 50 years, Japan built an empire that stretched from northern Manchurian down to the tip of Australia. Though its existence proved ephemeral, this was a staggering accomplishment for an island nation that had remained largely (though not completely) disconnected from the Western world until the mid-19th century and had only begun to modernize in 1868. In Japanese Imperialism 1894-1945, W.G. Beasley provides an overview of Japanese territorial expansion and imperialism, beginning with the Sino-Japanese War and ending with Japan’s defeat in the Second World War. In Beasley’s own words, the thesis of this book is as follows; “I do not believe the human impetus towards imperialism needs explaining…What the character of a society, or the international circumstances with which it has to deal, does indeed determine the timing and direction of the impetus, the degree of its success or failure, the kind of advantages that are sought, the institutions that are shaped to give them durability…That is what I propose to examine with respect to Japan” (Beasley, 13). This thesis struck me as vague and somewhat ill-defined. Essentially Beasley does not intended to examine why Japan attempted to carve itself an empire out of East Asia but how it did so. Much of this book is merely a summary of the conventional narrative on the subject with exhaustive references to names and dates. Ultimately, Beasley does not substantially contribute to the historical debate on the subject and merely synthesizes existing lines of thought. Upon turning the last page, the reader knows nothing more than the standard facts and is left to wonder what the point of picking up the book was in the first place.

危ない義理のできる男色

Oshima Nagisa’s 1999 film Gohatto is about desire and suspicion within the ranks of the Shinsengumi during the bakumatsu period. The film can be interpreted as both an examination of the destructive effects of desire within the brotherhood of the militia and as an allegorical criticism of the way modern Japanese society forces individuals to repress their desires for the sake of the group. While the second interpretation is entirely subjective, it is not unlikely given the fact that the director, Oshima Nagisa, commonly uses historical settings to criticize and examine modern society within his films. Furthermore, his failure to accurately reconstruct the sentiments of Tokugawa samurai during the mid-19th century within the film implies that Oshima Nagisa was more interested in using the subject matter to criticize modern society than in accurately reproducing the mentality of the time. It is clear that historical accuracy was not the primary concern of the director. Though Gohatto accurately portrays the environment and the official attitude of Tokugawa lawmakers towards shūdō (male-male relationships), its characters view the subject with an attitude that is far too modern.

A few days ago, I read the article “Finding Sparks Rethink of Russo-Japan War” in the Yomiuri (Link to original article HERE). According to some new documents discovered by University of Tokyo historian Wada Haruki, a key Russian politician attempted to propose an alliance with Japan in the days leading up to the Russo-Japanese War. The article reports that Aleksandr Bezobrazov, a man who has long been considered an advocate of the conflict, first communicated the draft “to Japan’s Foreign Ministry by telegraph on Jan. 1, 1904, by a Japanese diplomat in Russia. The diplomat reported to the ministry in detail about the proposal 12 days later…Despite the tip, Foreign Minister Komura Jutaro met with Prime Minister Katsura Taro, along with the ministers in charge of the army and navy, on Jan. 8, when they agreed to initiate hostilities.”[i] The article concludes that this new finding could lead to a revision of the widely-accepted interpretation that Japan was goaded by Russia into starting the conflict. This may also attract attention in Japan because NHK just started airing a three-year drama series based on a saga by novelist Shiba Ryotaro that depicts the Russo-Japanese War as one of self-defense by Japan.

Bushido: The Soul of Fanaticism

Hara-kiri’s Juxtaposition of Sensationalism and Reality

Anyone vaguely familiar with Japan has no doubt heard of samurai, the fiercely disciplined and loyal warriors who ruled over Japan for centuries. In the West, we like to believe that every samurai lived according to the philosophy of bushido, the Way of the Samurai. According to Japanese works, such as Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s Hagakure and Yukio Mishima’s Patriotism, this belief is quite accurate. However, what many fail to realize is that these works are a misrepresentation of the samurai beliefs common during the Edo period (roughly 1600-1868) and exaggerate the historical and social significance of bushido. In reality, bushido is an artificial philosophy, written and followed by a fanatic minority who wished to cling to a bloody, militant past and was never accepted or followed by the majority of the samurai class. In Death, Honor, and Loyalty: The Bushido Ideal, G. Cameron Hurst states, “The few Tokugawa works which explicitly use the term bushido turn out, in fact, to be a very narrow stream of thought essentially out of touch with the broader spectrum of Neo-Confucian ideas to which most of the samurai class adhered” (515). However, the principles of bushido – and samurai philosophy in general – are unclear and poorly defined because they were never codified into a written ethical code. For the sake of clarity, this essay will concentrate on the interpretation of bushido found in Masaki Kobayashi’s 1963 film Hara-kiri, which artfully juxtaposes the fanatic bushido followed by the Iyi clan and the more moderate and rational actions of the ronin Tsugumo Hanshiro. While Tsugumo’s actions seem to conflict with the principles of samurai ethics according to bushido, they are actually a more realistic representation of the principles upheld by the samurai of that time. The ‘philosophy’ of bushido misinterprets these values in several ways; it completely disregards compassion as the key element in the virtues of honor, loyalty, and duty, has a rabid philosophy of ‘pure action,’ and has perverted an ‘acceptance of death’ into an obsessive cult of ritual mutilation and suicide.

The fourth episode of my Japanese film series can be found on my YouTube channel. I have also included a critical review of the film.

Shin Heike Monogatari Review

The 1955 film Shin Heike Monogatari follows the Taira clan’s early rise to power. It focuses on the political elements of the consolation of power around the Taira clan as well as the personal relationships between the main characters. Like the original manuscript of the Heike monogatari, the film idealizes the virtues of the samurai and cannot be considered completely accurate. However, despite some romantization, the film ultimately presents a fair depiction of samurai during this period, particularly their comparatively low social standing and the absence of a fully developed sense of a collective group identity.

Recent Comments