For the second installment of my interview series about teaching in Asia, I sat down with my friend Nino. Nino and I both attended Boston University and shared several Japanese classes with each other. Since I always thought he was much too cool and good-looking to talk to, I actually didn’t get to know him until the Spring semester of my Junior year. So, I am definitely glad that a fortuitously placed copy of Karl Friday’s Hired Swords: The Rise of Private Warrior Power in Early Japan led to a conversation with him – he is one of the most intelligent people I have ever met and his knowledge of Japanese history is astounding. I can honestly say that he knows far more about samurai history than I ever will. Nino graduated from BU in 2009 with a degree in East Asian Studies and a concentration in Japanese. He has been teaching English in Japan since January 2010, first in Ishinomaki and later in Sendai City.

Constantine: So, why did you want to teach abroad?

Nino: Sadly the answer to this is more for the selfish reason of pursuing my own interest in Japanese history than anything else. Though, I do find teaching to be a fulfilling job, especially when you notice how much the student has learned. But, initially my passion for Japanese history is what brought me here; considering there’s no better place to study the history of a country than in that country itself.

Constantine: What sparked your interest in Japanese history?

Nino: Damned if I know. I first became interested in middle school… I have always been quite the nerd. The answer I usually tell people is Shogun by James Clavell. But, as an academic, admitting Shogun was my inspiration is actually sort of embarrassing – considering it’s such a bastardization and romanticized version of history – even if it was written as fiction. But in any case, I read it in middle school and knowing it was based on history got me interested to learn the actual history. I had always been familiar with samurai just from the general fantasy genre (which might often blend Eastern and Western mythologies or histories together) but after reading Shogun, it was the first time I actually began to pursue an academic interest.

Constantine: Shogun was actually something that sparked my interest in Japan as well. I read it at around the same age you did.

Nino: Yeah, I hate admitting it, but that’s what did it.

Constantine: It’s better than Sailor Moon.

I was recently asked to answer a few questions for the new website iShare-Japan about my experiences since I have moved to Japan. As some of you know, I have lived in Japan for almost a year; my so-called ‘Japaniversary’ will be on August 3rd. That’s no where near long enough to have developed a deeply nuanced understanding of Japanese culture (years of research on the country notwithstanding). I found this the most difficult question to answer: “What are some of the worst things about living in Japan?”

My mood routinely fluctuates between obscene love for Japan, disbelief that I am actually living here, and irrational frustration towards everything Japanese. The truth of the matter, though, is that living in Japan is now my daily life. That makes it difficult to identify if the problems I encounter are unique to my geographical/cultural location or merely representations of the difficulties everyone encounters from continuing to breathe.

Upon closer examination, I realized that there is a very easy way to depict the challenges I have faced since coming to Japan.

I am going to tell you something about myself that is readily apparent to anyone with eyes: I have been lucky enough to live a privileged life (and continue to do so). I come from an upper-middle class background, I attended a respected private university in the East Coast, and I conform to nearly every societal beauty standard without much difficulty – I am not fat, I am tall, I maintain a decent standard of athleticism, I have blonde hair, blues eyes, and, above all, I AM WHITE. In truth, the only institutionalized difficulty I may have faced in America is that I am female. And let’s face it, gender is less of an obstacle in America than most places in the world. That said, I’d also like to point out that the rest of the blog will be draw from my personal experiences, which are influenced by my privileged background. I cannot speak for anyone but myself.

What I’m getting at is that I have come from a culture of white privilege. Feminist writer Peggy McIntosh has written about the subject of white privilege extensively, and I will draw from her essay on the subject throughout this blog. She accurately sums up my life in America as such;

I see a pattern running through the matrix of white privilege, a patter of assumptions that were passed on to me as a white person. There was one main piece of cultural turf; it was my own turn, and I was among those who could control the turf. My skin color was an asset for any move I was educated to want to make. I could think of myself as belonging in major ways and of making social systems work for me. I could freely disparage, fear, neglect, or be oblivious to anything outside of the dominant cultural forms. Being of the main culture, I could also criticize it fairly freely.

When I moved to Japan, the privilege that I unconsciously lived with for my entire life was thrown out the window. I moved from being a member of ‘the dominant cultural form’ to being a minority. This will happen to everyone who moves to Japan who is not Japanese. Most of the complaints I hear from foreigners about living in Japan are directly related to this.

Peggy McIntosh outlines a list of 50 Daily Effects of White Privilege. All of these will be reversed when you move to Japan. Let’s take a closer look at some of them:

Every person why applies to the JET Program knows that they are going to be assisting in teaching English in some way during their time in Japan. The title ALT can mean anything from BigDaikon‘s infamous ‘glorified tape recorder’ to being given the responsibility of designing and teaching all of your classes (which is my situation…lots of work and a steep learning curve, let me tell you!). But something that I definitely DID NOT expect to find myself doing was giving JAPANESE LESSONS.

One of my schools has a heavy ‘international’ focus. Part of this involves the school not only sending students to study abroad (in places like Switzerland as well as the US). It also means that every year a new international student is brought to study at the school and live with the Japanese students in the dorm. Last year’s student was an extremely smart Korean girl who not only spoke fantastic Japanese but near-fluent English as well. She came to speak with me every day after school and I really loved listening to her whip out slang from episodes of Gossip Girl. Seriously, I had to start watching the TV series so that I could keep up with her…and to be able to field her many questions about American culture and teenagers. No, not all American teenagers are drug addicts. No, American teenagers do not leave school and head directly to the nearest swanky bar and knock back martinis. On a side note, this is probably the only time in my life that people will tell me that I look like Serena van der Woodsen.

But, I digress.

The new international student is an equally bright boy from Vietnam. Yesterday, my favorite English teacher came to my desk and asked me if I would help teach him Japanese every Wednesday after school. My initial reaction was something to the effect of:

“Are you joking? No one should ever learn Japanese from me!”

Sounds like a case of the blind leading the blind here…or more accurately, a retarded blind person (namely me) leading an unsuspecting victim off a cliff. The reason why this situation came about is because the new exchange student can’t speak any Japanese but CAN speak excellent English. So, the Japanese English teachers have taken him under their wing. Unfortunately, none of the English teachers have any experience teaching Japanese (or taking Japanese lessons, obviously). And thus they turn to me – the retarded blind person.

Now, before you go off criticizing the Japanese education system or the JET Program, I want to say that this isn’t really a bad idea. Not only do I have a large amount of Japanese language textbooks lined up of my bookshelf, I have also taken three years of Japanese lessons. More importantly, my role here is more to provide moral support and a break from his mandatory three hours of sitting in the library studying Japanese from a textbook every day. I know exactly how much fun sitting alone in a room with a Japanese textbook for hours can be…NONE. On top of this, these lessons take place after school on a purely volunteer basis. Today was our first Japanese class and I made it clear that, while I would be helping Sensei teach him Japanese, I would also take the role of a student in this class. I will be doing all of the homework and tests alongside him.

I have to say, I have enormous respect for this kid and his determination. He can’t speak any Japanese. At all. Other than two months of studying from a textbook, he hasn’t taken any Japanese classes. He can read hiragana, some katakana, and no kanji. And yet he was brave enough to come to Japan and study abroad in a Japanese school for a year. When I was his age, just going to my private Japanese tutor’s house every Sunday was enough to make me a nervous wreck. AND, when it comes to our Wednesday classes, he is not only trying to learn Japanese from scratch but he is also having it explained to him in English, another foreign language! Writing this fills my head with terrifying images of me being taught Japanese in German. Terrifying, I say, absolutely terrifying!

We’re starting from Chapter 1 and 2 of the first volume of Genki, the textbook series that I used during my first two years of Japanese classes in university. This chapter covers the most elementary basics of Japanese grammar, like:

__X__ は__Y__ です。 As in: 私はコンスタンティンです。

What really surprised me is that, halfway through an explanation about conjugating Japanese verbs, I realized that I’m not as inept as I thought I was when it comes to Japanese. Don’t get me wrong, I’m definitely inept – just not completely inept. I tend to think that I can’t speak Japanese until I open my mouth and Japanese pops out. Looks like this is another lesson in “Constantine needing to relax, stop worrying, and just do it.” That’s my life, a perpetual Nike advertisement.

Last Updated: Sept. 4th, 2010

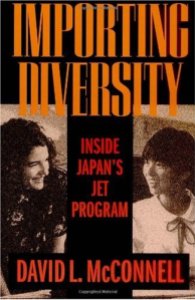

A Note: Please keep in mind the information in this post is based on the content found in Importing Diversity: Inside Japan’s JET Program by David L. McConnell – one of the few published academic studies of the JET Program. Throughout this post, I continuously note when the data was collected (the 1980s-1990s) and that it might not be reflective of the current selection process of some or any of the Japanese embassies or consulates that conduct interviews. This entry is not meant to serve as a definitive guide to the application process or as a list of the exact criteria JET candidates should fulfill. It’s just here to provide a bit of information to people who are interested in reading more about the application process. While I find the information within this article to be a fairly accurate representation of my experiences with the JET Program, please keep in mind that both the JET Program and it’s participants are a very large and diverse group. As such, the selection process seems to vary widely between individual consulates and between different countries. I don’t wish to encourage or discourage anyone for apply to JET with this post – I simple want to present a little bit of information on a process that many find extremely daunting, long, and fairly mysterious. ~C.

When I began applying to the JET Program in the fall of 2008, I spent a lot of time online trying to find information about how the JET selection process actually works. While the official JET Programme website, the AJET website, and every website for the consulates involved in the program all contain some information on the process, none of them actually get into the specifics of how JET goes about selecting candidates. Most of the websites just tow the party line, which goes something like:

“The recruitment and selection of JET Programme participants is conducted by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and is based on guidelines set by the Ministry of Public Management, Home Affairs, Posts and Telecommunications. (The number of participants from each country is determined according to the needs of the local governments in negotiation with the Ministry of Public Management, Home Affairs, Posts and Telecommunications.)

The final decision regarding acceptance of candidates is made at the Joint Conference for International Relations where the three Ministries (Ministry of Public Management, Home Affairs, Posts and Telecommunications, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) and the Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR) meet.”[i]

In other words, they don’t tell you a whole lot about how the selection process actually works and the criteria they use to accept people is somewhat unknown. After acceptance or rejection, most people just forget about the whole application process and don’t write about it anymore. But, something about its extremely opaque nature has always rubbed me the wrong way. I think that it is this opaqueness that makes the long selection process so uncomfortable for the applicants, especially for people like me who tend to micro-analyze things. So, I set out to find out more on how JET actually selects candidates.

Unfortunately, there isn’t a lot of information out there. The best study of the JET Program is undoubtedly Importing Diversity: Inside Japan’s JET Program by David L. McConnell. While discussing his methodology, McConnell accurately points out that “I found negotiating access to Ministry of Education and CLAIR officials and gaining permission to observe national-level conferences quite difficult; a general ministry policy forbids any outside research on the JET Program.”[ii] The fact that outside research is prohibited, while not at all surprising, does a good job explaining why it feels like so much of the JET Program is shrouded in secrecy. Before you start demanding more transparency, keep in mind that this is not an entirely abnormal policy for a Japanese ministry to adopt…it just makes the application process more frustrating.

The following information draws heavily on the research in David McConnell’s book. Importing Diversity is the best book I’ve ever read about the JET Program and I think that it should be required reading for anyone who participates or applies to the program. However, the biggest problem with this information is that it is outdated. It was published in 2000 (making it at least 10 years old already) AND the book examines the early years of the JET Program. JET began in 1987, which officially makes the program as old as I am. Any organization that has operated for that long is bound to have undergone some operational changes. Therefore, it’s impossible to know just how outdated McConnell’s description of the application process actually is.

I still think that the information in his book is extremely valuable to potential JET applicants. In fact, my own experience with the application process and the information in Importing Diversity are extremely similar. Still, be sure to exercise your critical reading skills with the rest of this post.

It’s February, which means that the Japanese school year is nearing an end. Last week, I had my final class with my 3 third year Advanced English students. These three boys are a really amazing bunch of kids, I was constantly impressed by their English abilities and interest in Western culture. They all wrote me farewell letters, which were funny and sweet. Here they are:

When I met you first, I just took a rest (lunch-time). Since I was poor at speaking English, probably I think you couldn’t understand it. But you managed to interpret what I said. When I knew you like horror movies, I thought you were a dangerous person. In fact, you are a good teacher. I remembered your making chocolate apples for us. We ate sashimi together in the library didn’t it? I remember well. You may forget us but I would like you to remember that we are your students. Thank you until now. That’s all.

When I first listened to you speak English, it was too fast for me to listen to your English. So it took me long time to make out what you say. But by you speaking English at natural speed, I have brought up my listening ability. This is so good for entrance examinations and my future. And I also had my essays checked by you. When I first had my essay checked, you added a lot of advice to my essay and a lot of English rules on another sheet. I have never had a teacher like you who inquired into it so closely. Thank you much, I sincerely appreciate it. Come to think of it, I regret not having my essays checked since you came here. But what I did makes for me a great deal. You like Japanese so much, and there are many Japanese cultures and many what Japanese made. I would like you to find them. The day will soon come when I learn a lot of your country’s cultures. So I have to study a lot. I hope you will succeed in everything and make your dreams come true. Thank you very much.

When you came to the school, I thought a model maybe came to it at first. When I was taken the first class, I was surprised because you learnt about Japan and Japanese things very well. Then, you showed us your home and the way you live in America. I was impressed with your stories that was different from Japanese ones in scale. The class looked like a party Halloween week was especially interesting. I enjoyed the special apple you made very much. I’m not a good student. I haven’t been what you expected to be. The only half-year has passed since we had met, you made me feel happy and motivated to improve my English. Thank you very much.

Awww, damn these kids, they make me want to cry.

This week is Christmas, so I’ve been teaching Christmas classes. This really just involves me having my students watch a segment from “A Sesame Street Christmas Carol” and baking them gingerbread cookies. (Hey, it’s the last class before winter vacation, if you think you’re going to get the kids to do any work you’re probably suffering from the side effects of a temporal lobotomy.) Most Japanese homes don’t have ovens, so being able to produce homemade cookies makes you a magician on par with Siegfried and Roy. Only without the tigers…and homosexual innuendo. But today was a pretty bizarre day…

First, I had three girl students give me a Christmas present and a homemade Christmas card where they wrote “You baked for us is cookies. Delicious. Please again. Thank you!” That was extremely sweet and touching.

Then, in class I taught the students the word ‘collection.’ For example, “I like Rilakkuma, so I collect Rilakkuma things. I have a Rilakkuma collection.” Then I asked the students if they collect anything. You can always count on boys to say something entertaining and two answers stuck out from the rest:

A) I collect girls. (Uh huh, sure you do.)

B) “I collect ‘good’ movies.” says the student.

“Really? What is the title of one?” I ask.

“Uh…it’s a secret…” says the boy.

“Do you have a hentai video collection?” I ask.

The class bursts into laughter.

Then, we watched two short videos about Hanukkah and Kwanzaa. In the videos, everyone is hugging. I explain that hugging is a part of American culture. On the way out of class, a boy student hugs me while his friends (and one of the English teachers) yell “SEKUHARA!” (Sekuhara is the cute Japanese way of saying sexual harassment). Then he ran away. Yeah, I told my students that hugging is ok in America, so I guess I had that one coming…

I also had a boy student say, “I love you” and run out of class. And people say Japanese kids don’t learn anything in school.

Later in the day, I had yet another boy student come up to me and say “Sensei, itsumo kawaii” and run away while his friend stared at me dumbstruck. Japanese high school boys have courage, but they really need to work on their follow through – running away isn’t going to win you a girlfriend.

After work, I had a police officer pull me over for exceeding the speed limit while passing a car (not out of the norm considering the way people drive where I live). But, he just said “Dame desu yo!” and made me promise not to do it again. Then he started talking about how he can’t speak English, but if he had a teacher like me when he was in high school he would have studied a lot harder. I gave him a cookie. Seriously, I gave him a cookie.

Then I went to the office New Year’s Party and gave out more cookies. And won a takoyaki grill in a quiz game because of my freakish knowledge of Japanese history.

Moral of the Story: Cookies is Japan are like volatile magic fairy dust…they both create problems and solve them. Either way, it’s bound to make the day more enterntaining.

My sannensei students sometimes write extremely adorable essays:

My treasure is this charm. This is the charm for entrance examination. When I was a junior high school student, I had a close friend. He was the most intelligent in the school. What he was intelligent was true, but he wasn’t earnest. He would often find fault with others, and he didn’t obey the school regulations. Anyway, he was not warm-hearted. But he was not always cold-hearted. He was kind to me occasionally. Informed of his leaving Oshima after he graduated, I felt bad a little. The graduation ceremony breaks up, he approached me, and gave me this charm. For I have talked with him about the university once. I never dreamed. I was glad to have given me all the more because he was cold-hearted. So this charm is my treasure.

Here are the answers to the questions that were asked to me in my interview and the sample questions I used to prepare for my interview!

I posted another JET Vlog about my thoughts on the JET Statement of Purpose

Here is my statement of purpose:

JET nearly gave me a nervous breakdown last week.

And I’d just like to state that I officially have the most patient and awesome boyfriend in the entire world. 本当にありがとう、ヒデ君!

When we interviewed in February, the people working at the consulate said that they would have the results out no later than April 10th. During the first week of April, I heard that all of the US consulates would submit the interview results at 5pm EST, Tuesday, April 7th. So I sat, glued to my computer, waiting…Waiting…WAITING. And nothing. On the JET forums, people were starting to post their results, but nothing from Boston! Then I heard from two of my friends that they had received their results (one waitlisted, one rejected). WHERE THE F**K WAS MY EMAIL?

Two days and a lot of lost sleep later, I find out that the server at the consulate crashed and only sent out 25% of the emails. I would have to wait for the post office to deliver my letter. I live on campus at a university. THIS TAKES A LOT OF TIME! By Monday, still no letter. I was driving Hide crazy and my only goal was to not burst into frustrated tears. After waiting so long, I had convinced myself that I had been rejected. The thing I’ve been wanting to do since I was twelve, denied! I called the consulate, but they wouldn’t tell me over the phone. Resigned to wait another day, I walk back to my computer and THERE WAS AN EMAIL! The server went back up! My results…SHORTLISTED!!

Soon I will be on my way to Tokyo for orientation…and then I will be shipped off to God-Knows-Where Japan to be the friendly pet foreigner for at least a year. YATTA~

So overall, what are my thoughts on the JET application process?

First off, it’s painfully long. I’m not certain if it’s absolutely necessary that the application process take 6 months (not including the paperwork you have to do after being accepted). But considering it’s operated by the Japanese government, the length of application period doesn’t surprise me. The Japanese government isn’t exactly the epitome of bureaucratic efficiency. Ha, bureaucratic efficiency, what an oxymoron.

However, even if the application process needs to be this lengthy, I’m not pleased about its very opaque nature. Ultimately, it seems no one knows why they pick the people they do. Sure, there is the laundry list of qualifications, but I’m already observed at least one PERFECT candidate be rejected. In short, its a black box. You put your application in, something happens to it inside, and then the results get spewed out the other end. JET does not publish how many people apply each year. They don’t publish how many get interviews or how many pass those interviews. They don’t publish how many people recontract. All they publish is the number of current JETs for each year and what country they come from. Hide says this is so they can express preferences (like ethnicity, age, etc) without the risk of getting sued for rascism/prejudice/etc. This makes sense. JET is a program about internationalization and cross-cultural exchange, but the Japanese schools want that exchange to be with a person who is obviously, if not stereotypically, American.

Don’t apply to JET of you need clarity or want to know some stats. They don’t give it to you. Everyone is frustrated by the end of the process. And that’s what makes getting accepted feel so good…because you’ve spent the last two months living in FEAR. That’s also why being waitlisted is ultimately worth it and still feels so good. The living-in-fear part has just been extended.

Now, I’ve got to get a physical, get fingerprinted, apply for an FBI background check, and IRS proof of residency, and a visa. But after all that, it’s NON STOP TO TOKYO ,BABY!

Recent Comments