Next up in the “Teaching in Asia” interview series is my friend Philip, who some of you may know as ToLokyo on YouTube. Philip graduated from university in 2003 with a degree in English Education – Secondary and a certification to teach grades 6-12 in Florida. During college, Philip did an internship abroad in Saipan. After graduating, he moved to South Korea in the summer of 2003 and started teaching English. Then, in mid-2005, Philip moved to Japan, where he made his living as a freelance English teacher until the summer of 2010. He is currently traveling around the world filming a YouTube video series called “Caught Doin’ Good,” that highlights individuals and organizations all over the world who are doing good things to build up the communities around them.. With seven years of experience living and teaching in both South Korea and Japan, Philip’s observations on living and working in Asia are extremely insightful and nuanced. Furthermore, as a formally-educated English teacher, his perspective on foreign-language teaching is much deeper than that of the average, run-of-the-mill ALT. He is also one of the most genuinely happy and fun-loving individuals that I have ever met; every time I see him, I am surprised by his positivity and enthusiasm. If you’d like to read more about Philip, his ‘Caught Doin’ Good’ project, or watch his YouTube videos, please follow these links:

Next up in the “Teaching in Asia” interview series is my friend Philip, who some of you may know as ToLokyo on YouTube. Philip graduated from university in 2003 with a degree in English Education – Secondary and a certification to teach grades 6-12 in Florida. During college, Philip did an internship abroad in Saipan. After graduating, he moved to South Korea in the summer of 2003 and started teaching English. Then, in mid-2005, Philip moved to Japan, where he made his living as a freelance English teacher until the summer of 2010. He is currently traveling around the world filming a YouTube video series called “Caught Doin’ Good,” that highlights individuals and organizations all over the world who are doing good things to build up the communities around them.. With seven years of experience living and teaching in both South Korea and Japan, Philip’s observations on living and working in Asia are extremely insightful and nuanced. Furthermore, as a formally-educated English teacher, his perspective on foreign-language teaching is much deeper than that of the average, run-of-the-mill ALT. He is also one of the most genuinely happy and fun-loving individuals that I have ever met; every time I see him, I am surprised by his positivity and enthusiasm. If you’d like to read more about Philip, his ‘Caught Doin’ Good’ project, or watch his YouTube videos, please follow these links:

Philip/ToLokyo’s website: http://www.locomote.org

Caught Doin’ Good homepage: http://www.cdg2010.org

ToLokyo on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/user/ToLokyo

Constantine: Why did you want to teach abroad?

Philip: When I graduated from university, I considered teaching around Asheville, NC in a high school. I knew I’d had enough of South Carolina and Florida, and I was ready to start something new. At that time, it was the beginning of the war in Iraq, and massive funds had been diverted from education programs all over the nation to be used in the war effort. I heard horror stories from friends who graduated the year before of having to teach with no textbooks or resources. In one fateful week, I randomly encountered about 5 teachers. They all had the exact same advice: “RUN~!!!! You’re young! You can do something else! You don’t have to be stuck in this hell of a job! Get out while you still can~!!!!” I took the hint and decided to look into a website I had heard of a few years back called Dave’s ESL Cafe.

Constantine: What sparked your interest in Asia?

Last Updated: Sept. 4th, 2010

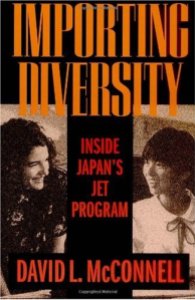

A Note: Please keep in mind the information in this post is based on the content found in Importing Diversity: Inside Japan’s JET Program by David L. McConnell – one of the few published academic studies of the JET Program. Throughout this post, I continuously note when the data was collected (the 1980s-1990s) and that it might not be reflective of the current selection process of some or any of the Japanese embassies or consulates that conduct interviews. This entry is not meant to serve as a definitive guide to the application process or as a list of the exact criteria JET candidates should fulfill. It’s just here to provide a bit of information to people who are interested in reading more about the application process. While I find the information within this article to be a fairly accurate representation of my experiences with the JET Program, please keep in mind that both the JET Program and it’s participants are a very large and diverse group. As such, the selection process seems to vary widely between individual consulates and between different countries. I don’t wish to encourage or discourage anyone for apply to JET with this post – I simple want to present a little bit of information on a process that many find extremely daunting, long, and fairly mysterious. ~C.

When I began applying to the JET Program in the fall of 2008, I spent a lot of time online trying to find information about how the JET selection process actually works. While the official JET Programme website, the AJET website, and every website for the consulates involved in the program all contain some information on the process, none of them actually get into the specifics of how JET goes about selecting candidates. Most of the websites just tow the party line, which goes something like:

“The recruitment and selection of JET Programme participants is conducted by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and is based on guidelines set by the Ministry of Public Management, Home Affairs, Posts and Telecommunications. (The number of participants from each country is determined according to the needs of the local governments in negotiation with the Ministry of Public Management, Home Affairs, Posts and Telecommunications.)

The final decision regarding acceptance of candidates is made at the Joint Conference for International Relations where the three Ministries (Ministry of Public Management, Home Affairs, Posts and Telecommunications, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) and the Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR) meet.”[i]

In other words, they don’t tell you a whole lot about how the selection process actually works and the criteria they use to accept people is somewhat unknown. After acceptance or rejection, most people just forget about the whole application process and don’t write about it anymore. But, something about its extremely opaque nature has always rubbed me the wrong way. I think that it is this opaqueness that makes the long selection process so uncomfortable for the applicants, especially for people like me who tend to micro-analyze things. So, I set out to find out more on how JET actually selects candidates.

Unfortunately, there isn’t a lot of information out there. The best study of the JET Program is undoubtedly Importing Diversity: Inside Japan’s JET Program by David L. McConnell. While discussing his methodology, McConnell accurately points out that “I found negotiating access to Ministry of Education and CLAIR officials and gaining permission to observe national-level conferences quite difficult; a general ministry policy forbids any outside research on the JET Program.”[ii] The fact that outside research is prohibited, while not at all surprising, does a good job explaining why it feels like so much of the JET Program is shrouded in secrecy. Before you start demanding more transparency, keep in mind that this is not an entirely abnormal policy for a Japanese ministry to adopt…it just makes the application process more frustrating.

The following information draws heavily on the research in David McConnell’s book. Importing Diversity is the best book I’ve ever read about the JET Program and I think that it should be required reading for anyone who participates or applies to the program. However, the biggest problem with this information is that it is outdated. It was published in 2000 (making it at least 10 years old already) AND the book examines the early years of the JET Program. JET began in 1987, which officially makes the program as old as I am. Any organization that has operated for that long is bound to have undergone some operational changes. Therefore, it’s impossible to know just how outdated McConnell’s description of the application process actually is.

I still think that the information in his book is extremely valuable to potential JET applicants. In fact, my own experience with the application process and the information in Importing Diversity are extremely similar. Still, be sure to exercise your critical reading skills with the rest of this post.

Recent Comments